Lockheed Martin has been having a tough year, losing out on new Air Force and Navy fighter contract opportunities in March and announcing $1.6 billion in Q2 losses in July. But the legendary aircraft manufacturer still has at least one technological ace up its sleeve: a highly classified aeronautics program that Lockheed CEO Jim Taiclet describes as a “game-changing capability.”

Details about this effort are exceedingly difficult to come by, however there’s a mountain of circumstantial evidence pointing toward one distinct possibility: a new intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and strike platform capable of penetrating deep into the most heavily contested airspaces to gather timely intelligence or conduct rapid strikes against targets that no other aircraft could reach.

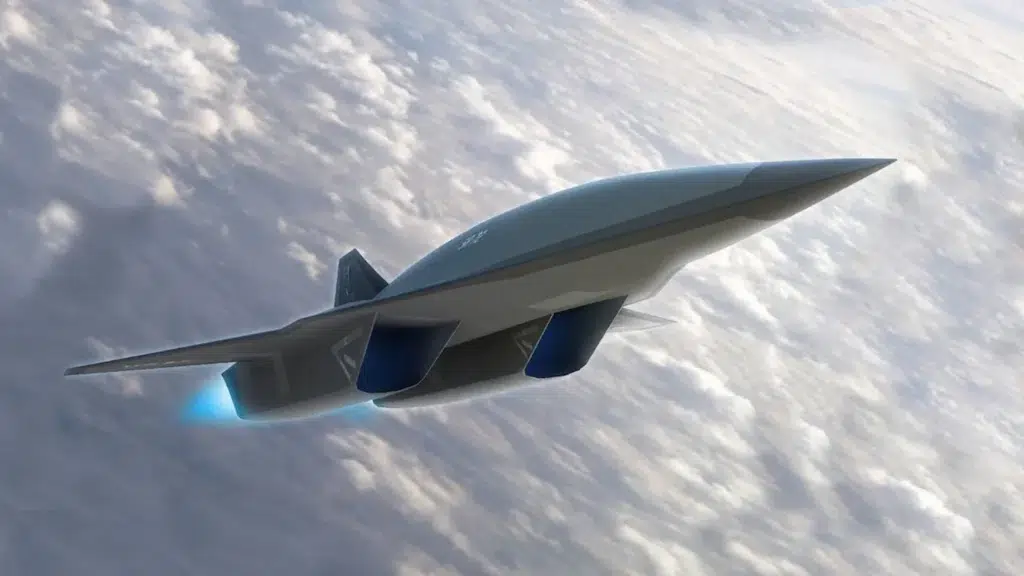

But rather than relying on extreme low-observability, as we’ve seen in other Lockheed Programs like the F-22, F-35, RQ-170, this new ISR and strike platform would see the return of brute force power, speed, and altitude to render enemy air defenses ineffective. It would scream across the sky at Mach 6 or more, altering its course at inconsistent intervals to make calculating an intercept course for surface-to-air missiles all but impossible, flying at altitudes no fighter could reach to intercept, and striking targets anywhere in the world with only a few hours notice.

Legends of a faster, higher-flying replacement for the SR-71 – dubbed the SR-72 – first began to emerge all the way back in the ’80s, with many arguing that the U.S. wouldn’t retire the spy plane without first having an even more capable replacement in service. The truth, however, was that the SR-71 was immensely expensive to operate, and popular misconceptions about the capabilities of spy satellites combined with advancing adversary air defense technologies led many lawmakers to believe that spy planes were quickly becoming a thing of the past.

Τhat belief would soon be proven very wrong, with the Blackbird’s first retirement only lasting five years before it was pulled back into active service in 1994, before being retired again in 1999 and very nearly brought back into active service once again in 2001. And since then, the United States has invested heavily into new ISR aircraft like the RQ-4 Global Hawk and highly-secretive RQ-180, while also funding significant upgrades for older ones, like the still-in-service U-2 Spy Plane.

That’s all to say that satellites are not the all-seeing, omnipresent eyes in the sky they’re often made out to be, and truly effective intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance can only be done through a combination of satellites and aircraft working in concert.

It was with this understanding that Lockheed Martin developed and fielded the once-classified RQ-170 Sentinel in 2007, known to some as “The Beast of Kandahar,” after pictures of the as-yet undisclosed aircraft emerged of it operating over Afghanistan in 2009. Northrop Grumman followed suit in 2010, with an even bigger and, arguably more secretive, stealth spy plane that we, in the public, usually call the RQ-180, but we still don’t even know what this flying wing’s actual designation is.

Most of America’s new ISR aircraft to emerge during the Global War on Terror were lower-cost non-stealth assets meant to operate in unconstested environments, like the MQ-9 Reaper. Yet, there was still an ever-present understanding that Uncle Sam would eventually need to be able to collect intelligence over more advanced adversaries.

And we now know for certain that, in 2006, Lockheed Martin secretly began design work on a spy plane unlike any other in history. This plane would use an exotic new propulsion system to scream through the sky faster than Mach 6, defeating enemy air defenses not through stealth, but through speed and unpredictability, just like the SR-71 did in its prime. This program, led by Lockheed Martin’s Hypersonics program manager Brad Leland, all but certainly related to a Lockheed patent filed that same year for a diverterless hypersonic inlet (DHI) for a high-speed, air-breathing propulsion system that “enables high vehicle fineness ratios, low-observable features, and enhances ramjet operability limits.” Leland, it’s worth noting, was one of the three inventors listed on that patent.

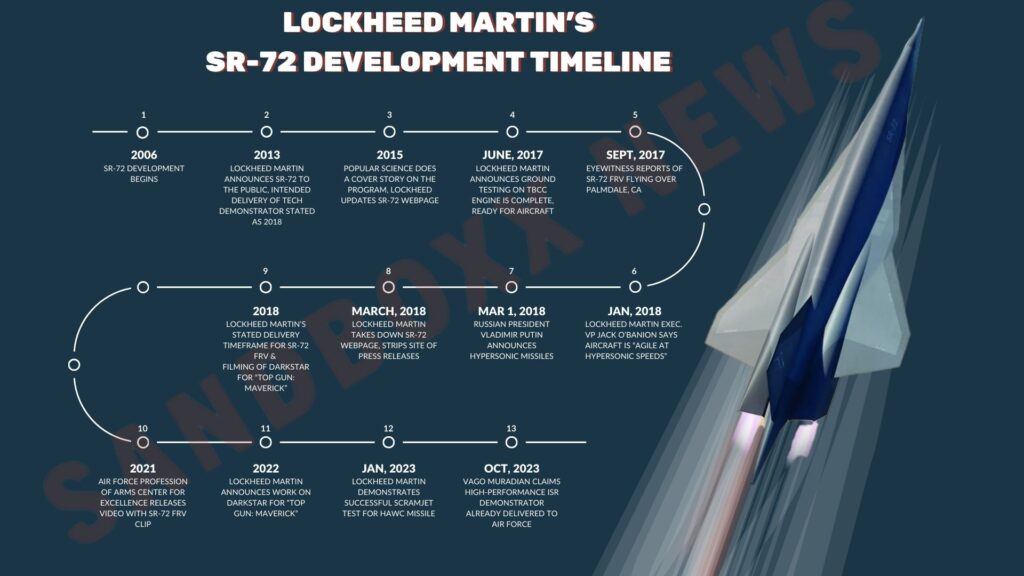

This work on the SR-72 would continue in secret until 2013, when the firm decided to make its progress public.

“Hypersonic aircraft, coupled with hypersonic missiles, could penetrate denied airspace and strike at nearly any location across a continent in less than an hour. Speed is the next aviation advancement to counter emerging threats in the next several decades. The technology would be a game-changer in theater, similar to how stealth is changing the battlespace today,” Leland said in a 2013 press release.

Leland went on to say that they believed they could have a single-engine F-22-sized technology demonstrator in the air by 2018, with the goal of having a twin-engine hypersonic ISR and strike platform in service by 2030.

In order to power this new SR-72, Lockheed partnered with engine manufacturer Aerojet Rocketdyne to build a turbine-based combined cycle engine. This is, in effect, two engines in one: a conventional turbofan for power at lower speeds, and a supersonic combustion ramjet (commonly called a “scramjet”) for high-speed flight. Turbofans function well from a dead stop up to above Mach 2, while scramjets don’t start functioning well until they’re moving at around Mach 3, so this design would allow an aircraft to take off and land under turbofan power, while using the scramjet to achieve hypersonic speeds (or speeds above Mach 5) in between.

This concept isn’t unique to Lockheed’s efforts. Hermeus has had a great deal of success with their Chimera turbine-based combined cycle engine that leverages a turbojet followed by a ramjet in recent years. Though, according to Lockheed Martin’s own press materials, they completed ground testing on their hypersonic engine design in 2017.

Related: Hypersonic firm Hermeus proves their Mach 5+ jet engine works

In June 2017, Lockheed Martin’s executive vice president and general manager of the Skunk Works at the time, Rob Weiss, told Aviation Week that they were ready to begin building that single-engine demonstrator before reaffirming a service target of 2030. Three months later, eyewitness accounts of what appeared to be that single-engine flight research vehicle began to emerge out of Palmdale, California, home to the Skunk Works.

When asked about these sightings, Lockheed’s executive vice president of aeronautics at the time, Orlando Carvalho, did not deny them.

“Although I can’t go into specifics, let us just say the Skunk Works team in Palmdale, California, is doubling down on our commitment to speed. Hypersonics is like stealth. It is a disruptive technology and will enable various platforms to operate at two to three times the speed of the Blackbird… Security classification guidance will only allow us to say the speed is greater than Mach 5,” he instead told reporters.

Then in January 2018, Lockheed Martin’s Vice President of Strategy and Customer Requirements in Advanced Development Programs, Jack O’Banion came right out and said the SR-72 demonstrator was flying at the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics’ SciTech Forum. He added that the digital transformation made it possible to 3D print the exotic engine with a sophisticated cooling system integral into the material of the engine itself, allowing for what he called “routine operations.”

When he was pressed about whether that meant the aircraft was flying, O’Bannion doubled down by saying “The aircraft is also agile at hypersonic speeds, with reliable engine starts.”

Two months after O’Banion made this claim, something of a modern hypersonic arms race kicked off with Russian president Vladimir Putin announcing the development of two new hypersonic missiles. Within a week of Putin’s announcement, Lockheed Martin had completely stripped its entire website of every mention of their SR-72 program pulling down its dedicated home page and every press release that even mentioned the effort.

You could argue that Lockheed decided to shelve the effort, but their statements in the months prior and the timing of the digital SR-72 purge probably point to the effort going dark instead, or continuing development in a classified setting, with classified funds.

Since then, hints of the SR-72 effort maturing behind the veil have bubbled to the surface from time to time, like a video released by the Air Force in 2021 that shows a very fleeting glimpse of a sleek, single-engine aircraft sitting in a dark hangar. When you slow the footage down and use video editing software to brighten it up, the designation SR-72 becomes visible on the fuselage.

Related: The SR-72 timeline: From initial design to ‘Top Gun’s’ Darkstar

And then, in the lead-up to Top Gun: Maverick’s release, Lockheed leaned hard into the idea that their fictional Darkstar hypersonic aircraft made for the movie may not be entirely fictional after all. “Darkstar may not be real, but its capabilities are,” Lockheed would say on social media posts; and the company later referencing the SR-71 Blackbird as the “fastest acknowledged crewed air-breathing jet aircraft.”

In November 2023, Vago Muradian, the editor-in-chief of the Defense & Aerospace Report, made a significant claim on his podcast.

“There is another program, however, which is for a much more capable reconnaissance aircraft that is the product of the Skunk Works and it is Lockheed Martin aircraft. There are articles that have already been delivered but that there have been challenges with that program. My understanding is that the program was re-scoped because it is that ambitious a capability that [it] required a little bit of re-scoping in order to be able to get to the next block of aircraft,” Muradian said.

This could certainly be in reference to the SR-72 program, with single-engine demonstrators representing the articles that have already been delivered, and the next block of aircraft meant to be the twin-engine operational platforms.

Yet, the part we should really focus on here is the claim that the program had to be rescoped because of its ambition. That suggests a program that’s running into engineering challenges, seemingly due to its technological complexity. And that brings us all the way back around to Lockheed Martin’s Q2 losses announced in July of this year.

From Lockheed Martin’s reported a $1.6 billion losses in the second quarter of 2025, roughly $950 million worth were associated with a single classified fixed-priced aeronautics program that saw “continued design, integration, and test challenges that had a greater impact on schedule and costs than previously estimated.”

And this were just the latest reported losses associated with this high-end, fixed-price effort.

In January 2025, Lockheed Martin reported another $555 million overrun on the same classified aeronautics program. These losses were attributed to “higher projected costs in engineering and integration activities that are necessary to achieve those forthcoming milestones,” though the milestones they referenced were not disclosed. Six months earlier, the company announced $45 million in cost overruns associated with the same project, and before that, they had already reported some $290 million in losses, again, tied to the same black project.

That puts Lockheed Martin more than $1.8 billion in the red on this single program; for a company that saw its profit margin drop by more than 30%, down more than $1.5 billion between 2023 and 2024, those losses are not something to scoff at.

However, the actual classified total cost is certain to be significantly higher than that. According to Lockheed’s financial disclosures, these overages are associated with a “fixed-price incentive fee contract involving highly complex design and systems integration.”

A fixed-price incentive fee contract, commonly referred to as an FPIF contract, is meant to incentivize contractors to keep costs down. These contracts are penned by the government and the contractors (in this case, Lockheed Martin), working together to determine a reasonable target cost for the platform and a reasonable target profit margin for the firm responsible for building it. That target cost and target profit are then added together to determine the target price for the overall program.

Then, a profit adjustment formula is established; we’ll use the 80/20 ratio shown in the federal government’s Defense Acquisition University breakdown. This ratio reflects how cost underruns or overruns will be shared between the contractor and the government, with the first figure (80) representing the government’s share and the second figure (20) representing the contractor’s.

So, let’s say a program has a combined target price of $1 billion, but Lockheed manages to deliver the aircraft $100 million under budget, for just $900 million. With a profit adjustment ratio of 80/20, that would mean the government would get to keep 80% of that $100 million in cost savings, or $80 million, while Lockheed would receive the other 20%, or $20 million, as a bonus for coming in under budget.

But the ratio works the same way with overages. If that same $1 billion program goes $100 million over budget, then the government would be on the hook to cover 80% of that overage, or $80 million, while the contractor, Lockheed, would only need to pony up the remaining 20%. This is meant to prevent a massive endeavor like, a hypersonic aircraft, from bankrupting the contractor and leaving the government with nothing to show for its investment.

There are limits to how much over budget such a program can go, and we call that the “Point of Total Assumption (PTA).” Once a program goes so far over budget that you reach the PTA, the government will no longer share the cost overages, and the company has to eat those losses entirely it. This is meant to protect the taxpayer, from paying into a failing effort forever.

Related: Lockheed Martin’s upcoming AGM-158 XR stealth missile is scary

Because the fixed price contract for this increasingly expensive aeronautics program is classified, we don’t know what the target price was that Lockheed has exceeded, and what the profit adjustment ratio and PTA is. Nevertheless, we do know that the effort has exceeded the budget by so much that Lockheed’s out-of-pocket penalty is now over $1.8 billion and may continue to climb. And if that 80/20 ratio was used in this contract, that would mean the added expense to Uncle Sam would be much higher – likely closer to $9 billion in overages alone. That could mean that whatever cost this program was initially projected to reach has already been exceeded by close to $11 billion. That is, unless Lockheed has already exceeded the PTA, at which point, they’d be eating any additional costs alone – and that is possible, considering initial losses were reported in the tens of millions of dollars per quarter until Q4 of last year, when they skyrocketed up to nearly a billion.

All of this points back to Muradian’s 2023 claim that Lockheed Martin’s ambitious new spy plane was facing challenges and needed to be rescoped in order to build the next block of aircraft. And that next block of aircraft could certainly be the twin-engine operational SR-72 platform that Lockheed has repeatedly claimed could be in service by 2030.

It’s clear that the research and development costs for whatever classified aeronautics program Lockheed has going on behind closed doors amount to far more than the reported losses associated with the program. We also know that in February 2024, the Air Force Research Lab opted to dramatically scale back funding for a separate air-launched hypersonic ISR platform being developed by Leidos under the name :Mayhem.” The Air Force cited a lack of “operational pull” to justify an acquisition program. That could suggest lost interest in high-speed reconnaissance operations or that another, more mature hypersonic platform was proving to be both promising and expensive, forcing the budget-strapped branch to pick one over the other.

Of course, there are other possibilities. Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works reportedly offered up an extremely high-end drone fighter design for the Air Force’s AI-enabled collaborative combat aircraft program that was deemed too expensive and “gold plated” for the first tranche of CCA contracts. Alternatively, this development funding could be going toward the most advanced autonomous fighter platform this world has ever seen. Or, maybe they’ve got something even crazier in mind.

But there is a distinct possibility that Lockheed’s legendary Skunk Works is burning whole heaps of cash building the SR-72: a successor to the reigning king of speed, the SR-71 Blackbird.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- The Alamo Scouts were a forgotten precursor of the Green Berets

- How US Special Forces took on Wagner Group mercenaries in an intense 4-hour battle

- The unsung heroes of World War II: The Ritchie Boys

- New material from North Carolina State University could revolutionize stealth aircraft (and even warship) design

- Ukraine reveals new long-range cruise missile that can strike Moscow