Airborne adventures with a Green Beret Combat Dive Team

- By George Hand

Share This Article

We had, at one time, a mission of parachuting into extreme cold waters. We didn’t have to travel far to find frigid bodies of water. Our choice at the time was the 58-degree waters of the Puget Sound in Washington state. In such water, an unprotected human has a life expectancy of approximately 20 minutes.

The rubber dry suits we wore in the Puget Sound were heavy and watertight.

Some time before the training mission, our technical officer sat with a salesman who hoped to sell to the Green Berets his company’s dry suit. The salesman remarked how easy it was to repair their dry shell – the suit’s external protective layer. He picked up a pencil and poked a hole through his suit’s dry shell and remarked:

“Watch how quick and easy it is to repair our product!”

Our officer pushed one of our dry suits in front of the salesman and invited him to just try and a poke it with the same pencil through our suit. Try as he may he could not achieve the same effect and humbly moved on. In our dive operations we traded comfort for durability. The tech officer rested his case; we stuck with our dry suits.

As the date of the jump arrived, the burning concern of the day was raised by our team medic, who postulated that during parachute operations and upon impact with the water the sudden squeeze to the suit from the impact would blow the neck seal, the suit would then flood with water, and we would subsequently sink from the weight of all the water and drown.

“Water doesn’t weight anything in other water, Mac,” our radioman told the medic.

“It’s evident in Archimedes’ principle of buoyancy,” he added.

Our A-Team commander agreed with the science and finalized it by saying: “We’ll all know for certain when we parachute into the sound wearing these suits, boys!”

That final word gave way to an airborne operation to jump wearing our dry suits into none other than Shark Drop Zone (DZ) of the Puget Sound.

Nerves were alive and firing briskly in their synapses. The science said the suits would not rupture and fill with drowning water, but the horror ran away with several of us.

Me, I just hated jumping, and beyond that you couldn’t pile more worrisome details on me to make the event worse. I surrendered to the notion that my suit would pop and I would sink… I just concentrated on the operation of my buoyancy compensating safety vest that we all wore – a Buoyancy Compensator, Medium (BCM)!

We jumped.

Related: Danger, Mines! Delta Force misadventures in Bosnia

Splash down!

My suit burped a large volume of air through the neck seal, which snapped back shut after the burp preventing any water from getting in. It was a piece of cake. One man wasn’t so fortunate; his wrist seal had a tiny tear in it which became enlarged when he impacted the water. His suit filled with water and he became neutral buoyant – not negatively as some had worried. But he still had to be pulled from the water immediately.

Our surface jump safety boat rallied and picked that man up. Although he was not a buoyancy risk, he had been subject to hypothermia from the frigid water that had entered his suit in about a half hour. He was hoisted up out of the water and drying out wrapped in wool blankets in no time. The rest of us formed a tactical swim formation and swam in to shore for a beach landing.

Know your equipment. Being technically and tactically proficient is key to success in combat.

By Almighty God and with honor,

geo sends

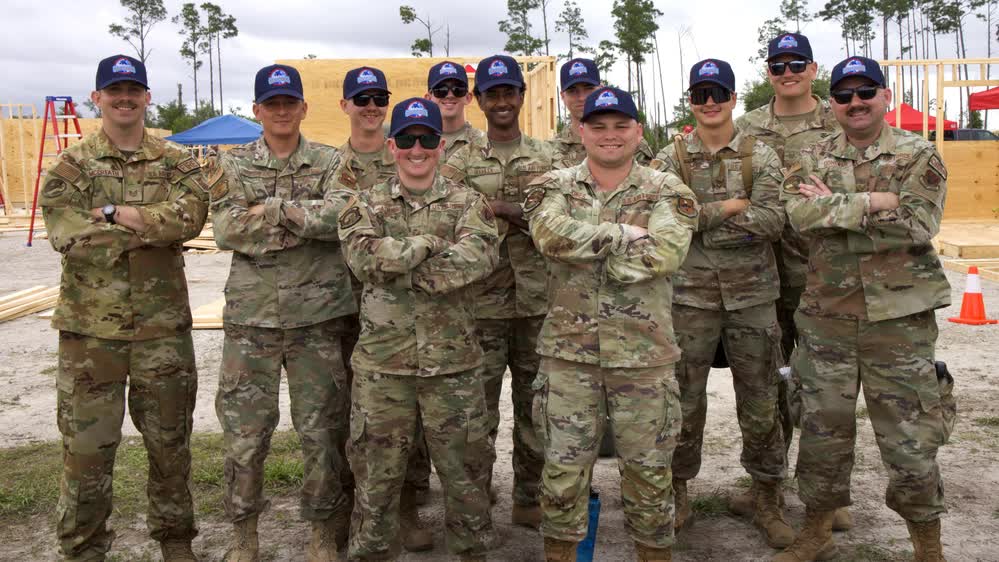

Feature Image: ODA-155 prepped for dive mission in the Bering Sea. Author in the center. (Courtesy of author)

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Martha Gellhorn: The only woman present on D-Day

- The special operations that paved the way for D-Day

- The Army is working on a next-gen smokescreen that can disrupt enemy sensors

- Tu-95 Bear: The ‘old’ Russian bomber that can’t be replaced

- Keeping it weird – The most bizarre features on military firearms

Related Posts

Sandboxx News Merch

-

F-35 ‘Evolution’ Poster

$22.00 – $28.00Price range: $22.00 through $28.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

A-10 ‘Thunderbolt Power’ Framed Poster

$45.00 – $111.00Price range: $45.00 through $111.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

George Hand

Master Sergeant US Army (ret) from the 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta, The Delta Force. In service, he maintained a high level of proficiency in 6 foreign languages. Post military, George worked as a subcontracter for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) on the nuclear test site north of Las Vegas Nevada for 16 years. Currently, George works as an Intelligence Analyst and street operative in the fight against human trafficking. A master cabinet-grade woodworker and master photographer, George is a man of diverse interests and broad talents.

Related to: Special Operations

Approaching Mach 2 in an F-16: ‘The jet started to shake’

7 strategies to stay positive in your military (or in any) career

Australian Abrams tanks in Ukraine may not affect the front-lines but they’re strategically important

SOCOM wants its secretive Long Endurance Aircraft drone to be able to launch smaller drones

Sandboxx News

-

‘Sandboxx News’ Trucker Cap

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Classic Hoodie

$46.00 – $48.00Price range: $46.00 through $48.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘AirPower’ Golf Rope Hat

$31.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Sandboxx News’ Dad Hat

$27.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page