- The App

- Sandboxx News

- Resources

Learn

- Company

About

Become a Partner

Support

- The App

- Sandboxx News

- Resources

Learn

- Company

About

Become a Partner

Support

Editor’s Note: This interview of Marine and Korean War veteran Charles U. Daly was written by his son, Charlie Daly. Charles U. Daly led a...

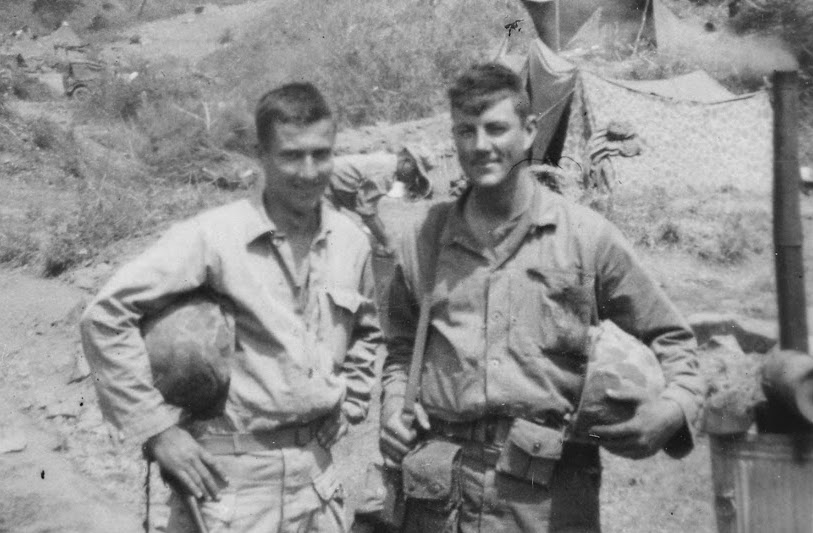

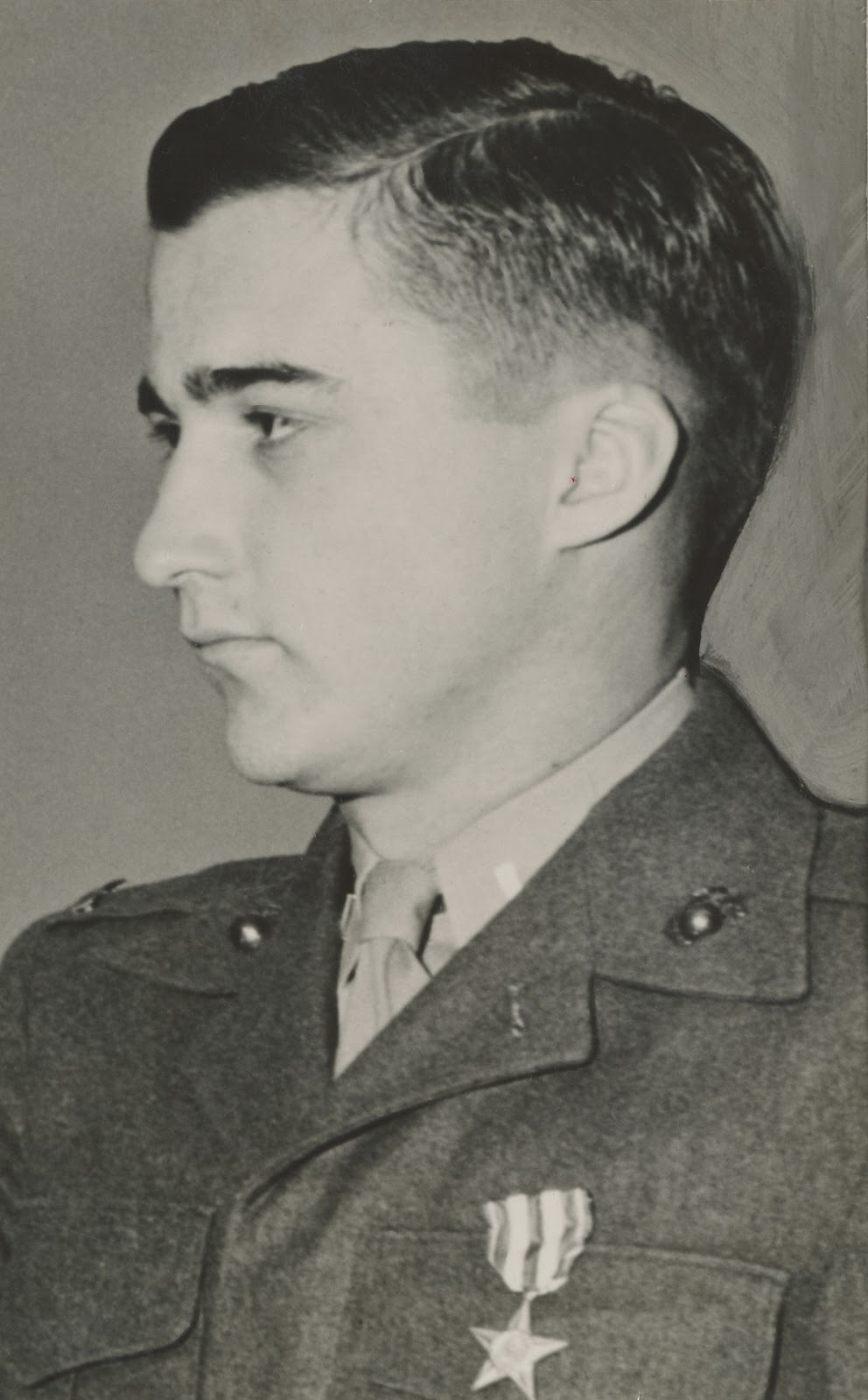

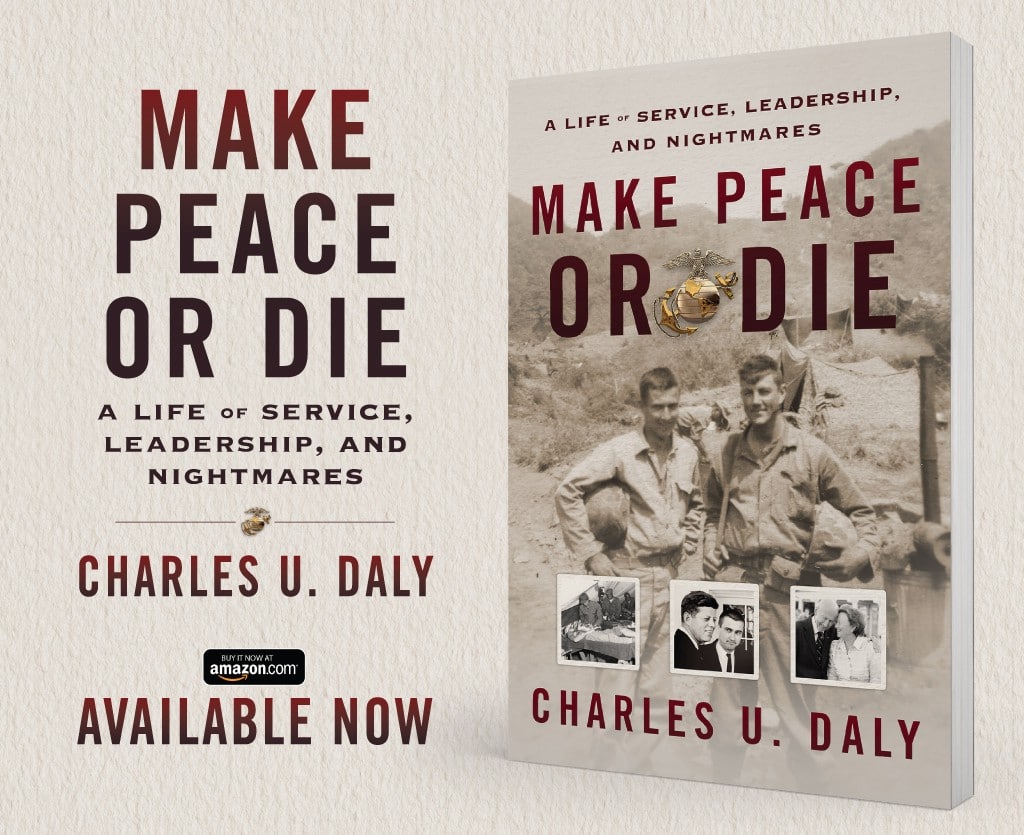

Charles U. Daly led a rifle platoon in Charlie Company, 1/5 Marines through some of the most intense combat of the Korean war. He received the Silver Star and Purple Heart. He went on to work for President Kennedy and is the last living member of JFK’s West Wing congressional liaison staff. He tells his story in the memoir, Make Peace or Die: a Life of Service, Leadership, and Nightmares.

What are your memories of mail while you were deployed?

I remember the lack of mail hurt some of my Marines. That’s a tough thing when everyone else is receiving mail, and there’s none for you. The guys who didn’t get any were stoic, and they didn’t show that it bothered them. They just turned around and hoped to get some another day, I guess. It was my job to lead them and look after them; I could make sure they had almost anything else they needed. But there was nothing I could do for a guy who hadn’t gotten a letter from home. I’d give those men anything, but I couldn’t give them that.

Chuck remembers one letter he wrote to his late wife, Mary, in which he joked about single-handedly winning the war. A couple of days after he sent it, the Chinese began the 1951 Spring Offensive, an unsuccessful attempt to win the war in 7 days, during which Chuck’s platoon in 1/5 Marines had to hold a hilltop, totally cut off from friendly forces.

On the night of April 21, I sent a note to Mary, brimming with overconfidence:

My Darling—

Just a note to say that I’m o.k.—We moved quite a way today & continue on tomorrow—w/any luck we should be north of Hwachon (sic), North Korea tomorrow.

I’m exhausted & will hit the sack—I love you, my wife—take it easy.

—Your mick

(Make Peace or Die, 60)

You got one very special telegram announcing the birth of your first son, Michael.

I had been anxiously awaiting that news, but I didn’t expect it to reach me the way it did, as a special message, hand-delivered by a runner. That was a note I won’t forget.

A runner followed Dacy and the replacements up the hill with a telegram for me:

PLEASE PASS TO LT CHARLES U. DALY 050418 X SON MICHAEL WEIGHING 5 POUNDS 12 AND 3/4 OUNCES BORN SATURDAY 19 MAY AT 2:06 PM X A BLACK-HAIRED MICK X MARY AND MICHAEL BOTH FINE X LOVE MARY

(Make Peace or Die, 80)

Pete had received news about a baby daughter two days before. Our platoons were delighted. They said, “we” made a baby. It was good news, and it was tough news. I folded up the telegram and put it in my wallet and thought it’d be nice to have if I made it.

Now that note belongs to Michael’s first daughter, my first grandchild, Sinéad.

What was it like trying to do your job as a platoon leader while you were waiting for that big news?

I was trying to concentrate on my responsibility for Marines in combat. When I had time to think, I thought a lot about my wife and my hopes for our family. But I knew that if I didn’t concentrate on the job, I would never get to fulfill those hopes.

You wrote to your father after the firefight for which you were awarded the Silver Star.

I wanted him to know I’d done well. In case I didn’t make it, I wanted him to know I had died trying. He had led a platoon in the First World War; I suppose I wanted him to know that I understood something of his experience.

Shortly after my own war, I asked Dad, “When do the bad memories fade?”

“It will take a long, long time, but finally they will fade.”

As of today, mine have not.

(Make Peace or Die, 23)

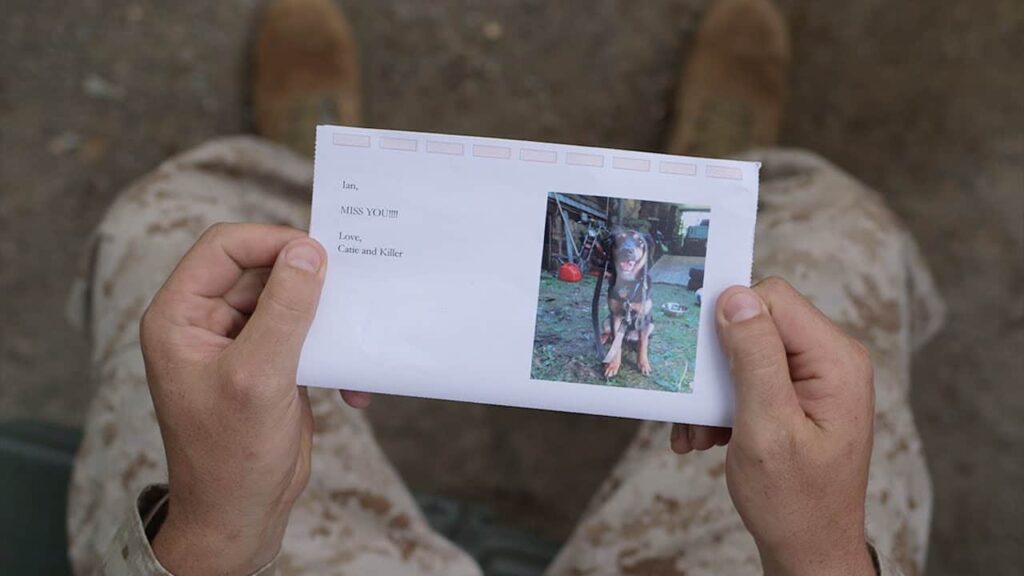

A few weeks later, you finally got Michael’s picture in the mail.

That was good. I noticed the Heath chocolate bar in the envelope first. The photo was a big surprise. I wish I still had it, but it got ruined by the melted chocolate.

The platoon sergeant and I laid-up in an abandoned enemy bunker… An attack on our position that night could have doomed us, but it didn’t come. I felt good. Even though I still had little hope of living to hold my son, a picture Mary had sent me of him had arrived in a letter enclosed with a melted Heath bar. Having seen my son Michael’s face, I suddenly had more to lose.

(Make Peace or Die, 97.)

Nowadays, a Marine in the field can sometimes send texts or make video calls. Sometimes, you can even get in touch with your family via satellite from the most remote outpost.

I can’t even imagine that.

What would be your advice to families writing to a loved one who’s downrange?

Start with good news. Try to have good news. Bad news can wait, but if you have to pass it on, be delicate about it. Life at home isn’t always going to be all lovely every day, but it helps to let your son or daughter or spouse know that everything’s alright and there’s no need to feel bad about not being home to deal with life’s little challenges. But I don’t think it’s possible to say the wrong thing. No matter what you write, your letter is going to be the bright spot in their day.

My one suggestion, based on experience: SAVE YOUR LETTERS! When we were working on my book, we managed to find a couple of my letters home, but most were lost to time. I don’t remember what I wrote.

Make Peace or Die: A life of Service, Leadership, and Nightmares is available through Amazon and Indiebound, or you can ask your local bookstore to order it. An early draft was featured on Jocko Podcast episode 196.