June 6, 1944.

Allied troops from Great Britain, Canada, and the U.S. stormed five beaches in Normandy in the largest amphibious operation in history. Operation Overload, colloquially knowns as D-Day, spelled the beginning of the end of Nazi Germany’s occupation of Western Europe.

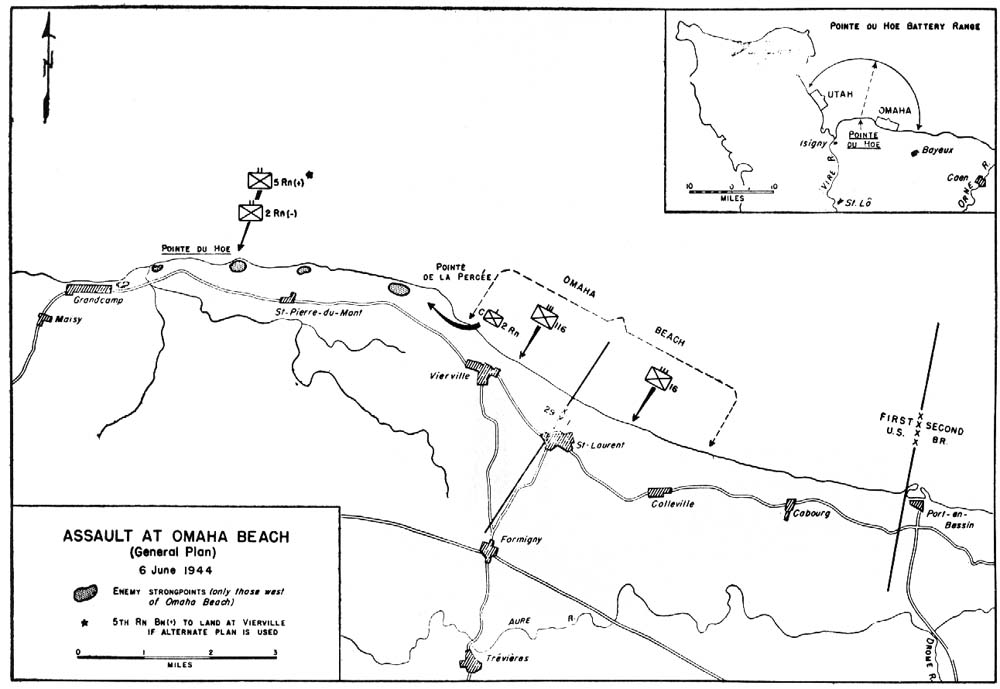

Codenamed Juno, Sword, Gold, Omaha, and Utah, the landing points stretched 50 miles on the coast of Normandy, in the north of France, just across the British Isles.

To get the men in France, the Allies marshaled an armada of more than 5,000 ships and 1,200 airplanes. By the end of June 6, more than 150,000 Allied troops were on French soil, and before the summer was out and a breakout from Normandy was achieved, that number would swell to close to two million.

On June 6, a lot of things happened. From sword-carrying, bagpipe-playing British officers charging German positions to the mayhem at Omaha beach — brilliantly portrayed in the Hollywood blockbuster Saving Private Ryan — to vastly outnumbered Germans fighting to the end, the day was packed with moments of courage and intrepidity, on both sides.

However, a series of special operations before and during D-Day stand out for their sheer audacity.

Scaling Pointe du Hoc

A strategic position, Pointe du Hoc was located right in between the two landing beaches assigned to the U.S. forces, Utah and Omaha. Utah was on the left, Omaha on the right. The Germans had fortified the position with artillery, which posed a deadly threat to the landing infantry on the beaches.

A solution was needed, so U.S. commanders turned to the Rangers: approximately 225 Rangers from the 2nd Ranger Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James Rudder.

At 0405 on the morning of D-Day, a few hours before the main invasion, hundreds of Royal Air Force bombers softened up the target area with close to 635 tons of ordnance, while the naval bombardment, which began at 0555, added more lead and explosives. But the German positions at Pointe du Hoc remained largely unaffected.

Related: Who actually gets to call themselves ‘Army Rangers?’

Sheer, 100-foot rocky cliffs were the best insertion point to the German positions. The Rangers used ropes and ladders to scale them while under constant fire from the Germans. Once on top of the cliffs, the Rangers stormed the artillery positions, which had been moved back to an orchard approximately 600 yards from the cliffs, and destroyed them. However, the Germans counterattacked, wanting to recapture the strategic position. Suddenly, the Rangers’ mission changed from destroying artillery pieces to surviving.

By the next day, D+1, only 90 Rangers were fit to fight. Fierce German counterattacks pushed the Rangers to their limits, many of whom were captured. It was only on the day after, D+2, that reinforcements finally arrived and the Rangers were relieved.

After the fight was over, Lt. Col. Rudder remarked, “How did we do this? It was crazy then, and it’s crazy now.”

Related: This incredible World War II hero was the first Navy SEAL

Pegasus & Horsa bridges

To be successful, the landings had to be quickly followed by an advance inland. The Allies could pour tens and hundreds of thousands of men into the five beachheads, but if they couldn’t find a way to funnel them through, all would be for naught.

Thus, several bridges and crossings further inland were deemed as strategically essential as the landings, and British and American paratroopers were tasked with securing them; essentially jumping behind enemy lines, and waiting for the advancing troops from the beaches.

The bridges on the Orne River (codenamed Horsa Bridge) and Caen Canal (codenamed Pegasus Bridge) were some of the more important, and the task of capturing them fell to the British Paras. They didn’t need to just capture them intact, they would also have to defend them.

Related: Pippa Latour: The WWII spy turned humble hero

Shortly after midnight on June 6, British Paras jumped or landed with gliders near the two bridges and captured them in a coup de main. The Germans were caught completely unawares.

Then, the British Paras had to wait until the troops from the beaches relieved them. But the landings were still six hours away, and the Germans were coming.

In an interview, Len Buckley, a British paratrooper who jumped on D-Day and fought at Pegasus Bridge, offered some unique insight on the night of the mission and also about the role of luck in combat.

“We landed about 40 minutes after midnight, just about 70 yards from the Bridge. After brief rendezvous in an orchard nearby, we had to go at the double onto the bridge to relieve the Ox & Bucks who had already taken the bridge. They had obviously had quite a fire-fight; we passed an armoured half-track on fire. Hit by a PIAT [hand-held anti-tank weapon, similar to the U.S. bazooka], the vehicle was exploding all over the place as its ammunition went off.”

Under pressure, we held the bridge from enemy counterattacks, but I took a bullet which was deflected off the butt of my Sten gun and then passed right through my elbow. If it wasn’t for that Sten, I would have got it in the chest. I was pretty lucky. They evacuated me back to the beach, through a casualty clearing tent and onto an LCT [Landing Craft Tanks]. There we were strafed by two German fighters – machine gun bullets hitting all around. The chap next to me was killed, but I was fine. Once again, I couldn’t believe my luck.”

Finally, on June 7, D+1, the British Paras were relieved, having held the German assault for 36 long hours.

The actions of the British Paras at the Pegasus Bridge remain alive to this day in the form of P Company, the selection and assessment unit responsible for selecting and training new candidates aspiring to become Paras.

Related: Operation Junction City: Vietnam’s only large-scale airborne operation

Preparing the operational environment for D-Day

Delaying the German response, especially the potent SS and Panzer divisions, from reacting quickly and wiping out the beachheads, was critical to the success of D-Day. To achieve that, the Allies deployed several small special operations teams in the days and hours prior to the invasion to coordinate with the French resistance and do whatever was possible to delay or deceive Nazi reinforcements.

The task fell to the commandos of the Special Air Service (SAS) and the Jedburgh teams.

Several SAS units, including the 1st and 2nd SAS (British), 3rd and 4th SAS (French), and 5th SAS (Belgian), parachuted into Normandy. In addition, Jedburgh teams from the U.S. Office of Strategic Service (OSS) — the predecessor of the Green Berets and the CIA, the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), and the French Free France Central Bureau of Intelligence and Action (BCRA) parachuted into the region to coordinate with the French partisans and direct their opposition.

The SAS operated in platoon- and company-sized elements, while the Jedburgh teams were composed of the three commandos, a team leader, an assistant team leader, and a radio operator.

The SAS fought directly against the Germans, while the Jedburgh teams fought indirectly — sometimes directly as well — through their local partisans.

Although their contribution is hard to quantify since they weren’t tasked with destroying artillery pieces or capturing bridges, both units contributed to the success of D-Day. However, they paid a heavy price as the Germans vastly outnumbered them, and any commandos captured were summarily executed.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in June 2022. It has been edited for republication.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Guile, violence, and intelligence – The tools of the WWII spy

- The INSAS – Is this the worst assault rifle ever made?

- Watch: Chinese warship nearly collides with US destroyer near Taiwan

- Which will be the company that will build America’s next stealth fighter?

- A-20: The forgotten bomber that wreaked “Havoc” in WWII