While much of World War II is well known and documented, there are stories and people who have all but slipped through the narrative cracks over the years. Does the name Virginia Aderholt sound familiar? She was actually the first American to learn that the war had come to an end. She received the intercepted message from Japan meant for Switzerland, and was responsible for deciphering the declaration of surrender. She was just one of an estimated 10,000 women tasked with decoding some of the most privileged military intelligence during the war. Opposite to the draft, this was a job they were all quite literally chosen to do.

Almost every story of a woman who became a WWII codebreaker starts virtually the same: an unexpected letter in the mail. It began with women at Seven Sisters, a set of seven highly regarded liberal arts colleges throughout Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania. These women were selected based on their academic prowess, particularly in subjects such as astronomy, foreign language, English, math, and history. After this initial contact, the women took part in additional “tests,” or screenings, to help determine whether or not they were cut out for the job. Some women were asked questions about prospective marriage plans, or if they enjoyed things like crossword puzzles.

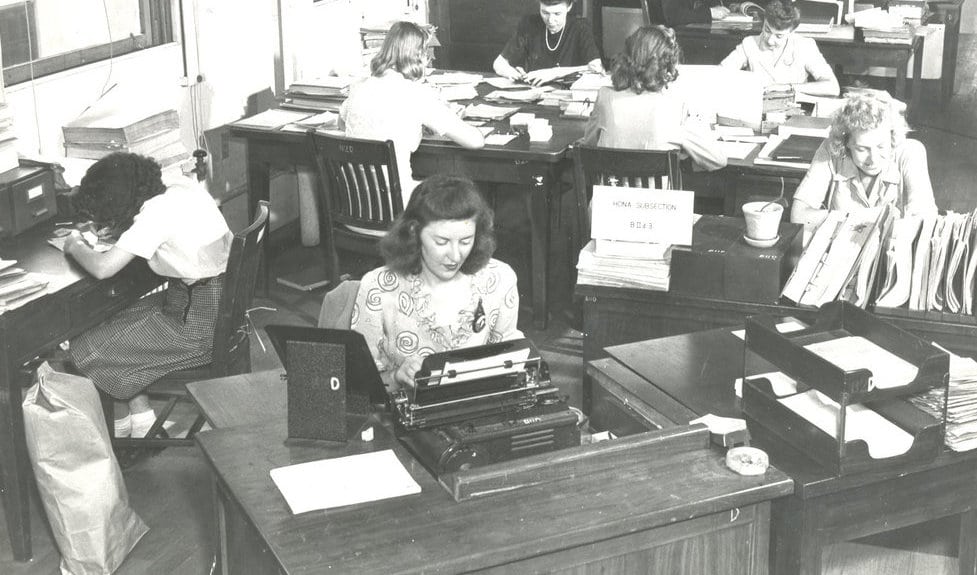

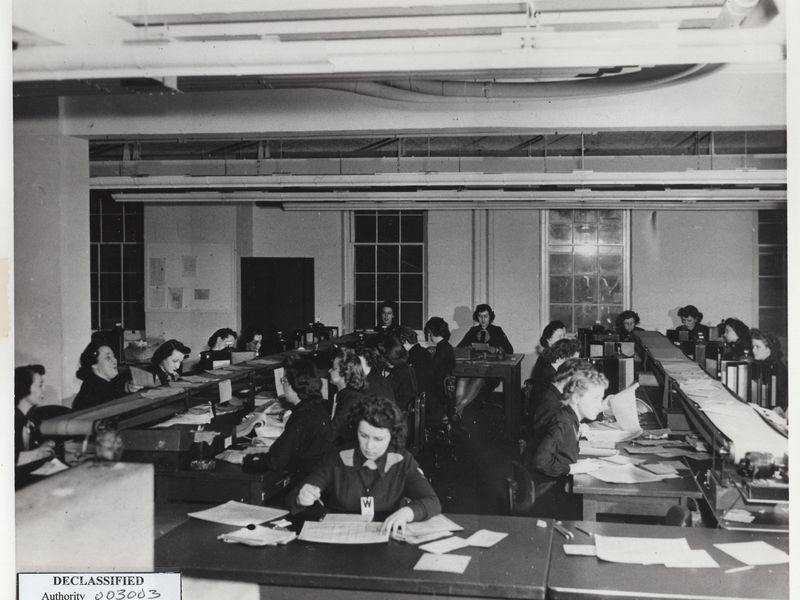

As time went on, the need for more assistance became apparent. Additional women were called upon, many of whom were approached because of their plans to become school teachers. The idea behind the widespread recruitment of women over men was for several reasons—the main one being the notion that men were needed on the battlefield. Some also saw the job itself to be inherently administrative, much akin to a secretary, which at the time, was a position almost exclusively held by women.

Initially, the codebreakers, brought in mostly by the Army and Navy, were still considered civilians. They would not be able to officially join and serve until 1942, and even then, there were considerable disparities. Unequal pay and benefits were issues, as well as criticism that there was little respect given to rank considerations. Despite the obvious need for their service and the value they held, women at the time were discouraged from serious careers, or job paths that were historically fulfilled by men.

The book Code Girls, written by Liza Mundy, interviewed around twenty of the original codebreakers and, among other things, talked about the day to day treatment and stigma of women in the military at that time.

“The women also had to constantly work against public fears of their independence. As the number of military women expanded, rumors spread that they were ‘prostitutes in uniform,’ and were just there to ‘service the men,'” Mundy says.

Related: THE EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S EQUALITY IN THE MILITARY

These women would be another step in the staircase being built for equal gender recognition and respect, both in the workforce as well as the armed forces.

For codebreakers, working a 9 to 5 would have seemed like a vacation. Twelve hour days were the norm, as were working seven days a week. The work was a perfect storm of tedious and complicated, testing even the strongest of mental faculties. They were expected to accurately and regularly break Japanese and German military intelligence communications that rarely remained the same for very long. The best of the best began to recognize common themes, even if the ciphers themselves changed.

One of those women was Genevieve Grotjan. Grotjan had been working for the government, calculating pensions, when the war broke out. This was after her hope of becoming a college math professor was met with numerous schools’ unwillingness to hire a woman for the teaching position. When her math skills at her regular job garnered a husband and wife cryptanalyst team’s attention, she was recruited as a codebreaker. She was instrumental in cracking Purple, which was a Japanese cryptography machine that the U.S. had been working to decipher for months prior to bringing her on board. Understanding the code of Purple was integral for U.S. intelligence moving forward. Grotjan, and so many like her, set the precedent that help can come from unexpected places.

When the war ended, the vast majority of these women quietly returned to their civilian lives, while a small handful went on to achieve higher ranking positions within the military. For both groups, it seems, stories of their code-breaking efforts were left widely untold. During their time of service, there was a widespread understanding that any and all information was privileged, and sharing it in any capacity was unacceptable. This notion carried over, back into civilian life, and throughout the lives of the “code girls,” who took much of what they learned and saw to their graves. It’s through the accounts of the few that we learn the story of the many, and we are able to amplify those stories to the volume that they deserve.

Related: WOMEN IN THE MILITARY: PAVING THE WAY AND SHOOTING FOR THE STARS…LITERALLY