Last week, U.S. Secretary of the Air Force Troy Meink addressed China’s rapidly maturing space program at the Spacepower conference in Orlando. He acknowledged that space is yet another theater in which China has relied heavily on stolen intellectual property and modeling its efforts after successful Western programs. But, he also cautioned against writing China’s space program off as a result.

“They are copying us in many ways. But don’t let that confuse you. They are very, very innovative as well. It’s not just copying us. They are super innovative in how they’re operating, which puts even more pressure on us to innovate faster,” Meink said.

This is a trend American analysts have seen across a breadth of industries: China’s intellectual property theft has progressed in parallel with massive investments in its education, research, and engineering infrastructure.

China doesn’t want to build a copy of the US military or the American space program: it wants to build its own, improved versions of each. China’s stated aim is to supplant the United States as the world’s preeminent superpower, and it knows it can’t do that through copying alone. It’s that goal that’s led to China’s heavy investment into this new space race.

Chinese officials have seemingly intentionally drawn direct parallels between Beijing’s lunar ambitions and its illegal claims over vast swaths of the Pacific Ocean.

In 2017, the head of China’s moon mission program, Ye Peijian, appeared on Chinese State Television and said that “The universe is like the ocean: the moon is like the Diaoyu Islands and Mars is like Scarborough Shoal. We will be blamed by our descendants if we don’t go there… and others get there before us.”

The Diaoyu Islands, as he put it, are disputed islands some 200 miles off China’s coast (and about 100 miles from Taiwan) in the East China Sea; the Scarborough Shoal is a coral reef atoll inside the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone that China has laid claim to anyway, despite being more than 500 miles from the nearest Chinese territory. In 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague ruled China’s claims over the shoal were illegal under international law, but China has ignored the ruling.

China’s lunar ambitions

China seems interested in lunar resources. There are several resources on the Moon worthy of direct competition, but none more valuable than the frozen water found in the deep craters of the Moon’s north and south poles. The hydrogen and oxygen that make up water are vital elements for the creation of rocket fuel. Being able to produce fuel on the Moon has huge advantages over doing so on Earth, as rockets could launch from Earth carrying only enough fuel to reach the Moon, and then be refueled in lunar orbit for follow-on destinations like Mars.

Because this frozen water is only found in specific places near the poles (known as permanently shadowed regions, or PSRs), American and European leaders are rightfully concerned that whoever reaches the Moon first in the 21st century will have “first mover advantage,” which basically means whoever gets there first not only claims the resources, but also gets to dictate norms moving forward. That would mean China could dictate how international relations on the heavenly body are conducted, giving it the opportunity to lay claims of sovereignty over strategically important or resource-rich areas, establish economic exclusion zones for future discoveries, and more. In effect, China gaining control over the moon could result in China keeping control over the Moon for the foreseeable future, barring some sort of direct conflict.

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967, signed by both the United States and China (among many others), outright prohibits claims of sovereignty over lunar territory and the militarization of space in general. Yet, China’s refusal to follow international law regarding Pacific islands, which it directly compares to its space aspirations, doesn’t create a great deal of faith in China’s willingness to adhere to the Outer Space Treaty.

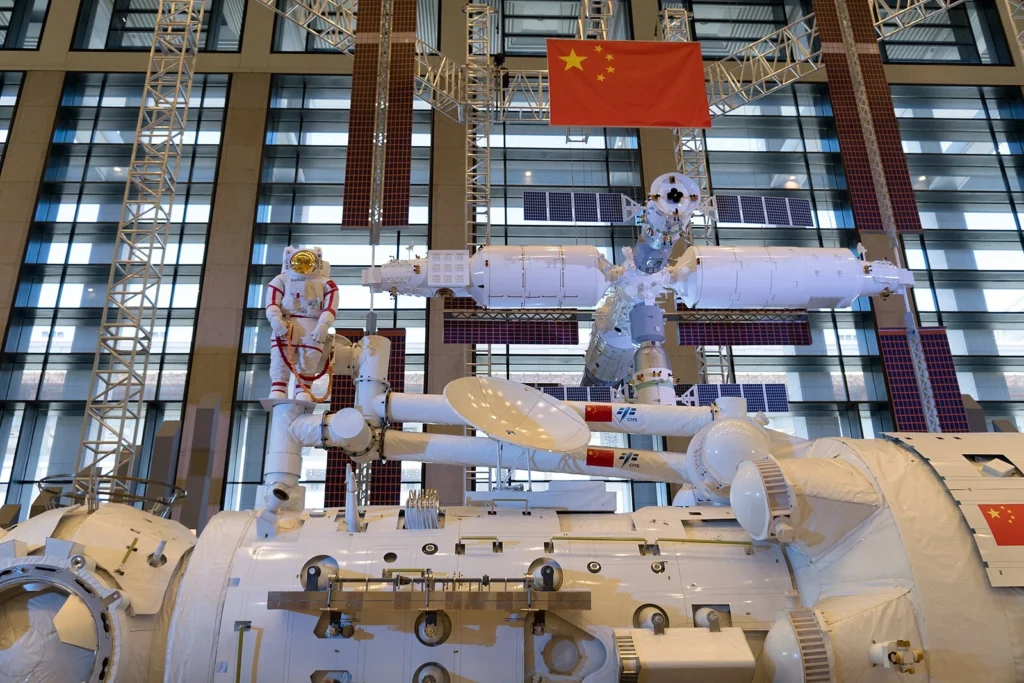

China’s military, the People’s Liberation Army, formally designated space as a warfighting domain all the way back in 2013, and the nation’s space program is a joint military effort, meaning there is no differentiation between organizations, unlike how America’s civilian NASA program operates independently from the U.S. Space Force.

In direct contrast, the American-led Artemis Accords, first signed in 2020, set out to establish best practices and international norms regarding the Moon which are predicated on “the benefit for all humankind to be gained from cooperating in the peaceful use of outer space.”

They emphasizes adherence to the Outer Space Treaty that bars any nation from laying a permanent claim to lunar territory or deploying military assets to assert sovereignty, while still allowing for things like resource extraction. Today, some 57 countries have signed the accords.

Some might argue that America is using its soft power to expand its hegemony to the Moon which is why it’s concerned about China’s lunar ambitions; and that Uncle Sam’s welcoming demeanor is more about distributing the immense cost of lunar operations between countries than it is about true space-based diplomacy.

They could be right on all counts. But that doesn’t mean an American-led victory in this 21st-century space race would be bad for anyone, other than perhaps China and its partners.

The future of humanity’s efforts in space will likely be largely dictated by the norms established by whichever country plants its flag on the Moon next. America has sought to involve as much of the democratic world in its efforts as possible, working to establish guidelines by which lunar cooperation could come to define the world’s space endeavors for a century to come. Meanwhile, China has openly compared the moon to territories it aims to lay claim to and militarize. Even if you don’t completely trust the former, it still sounds a heck of a lot better than the latter.

Does it even matter?

The bigger question is just how important is the Moon really when it comes to the balance of power in the decades ahead. Is it worth investing hundreds of billions of dollars to establish a presence there and continue on to greater challenges like Mars and beyond? Or should the Western world let China claim ownership over it? It depends a bit on where your priorities lie.

Ceding the Moon to China could lead to orbital disadvantages in the long run, as China’s space presence would swell in the absence of competition. Technologies developed in the pursuit of establishing permanent or semi-permanent colonies on the Moon could provide China with the means to erode America’s technological advantages in other military or commercial domains. Further, a Chinese victory in this modern space race could create immense soft-power advantages – in all the same ways it did for the U.S. during the Cold War – towards the rest of the world.

On the other hand, one could argue that there are other lines of effort more deserving of American funding that the new space race; other threats more pressing; or other goals more worth pursuing.

But the problem with these discussions is that we’re comparing immediate to long-term concerns. For example, today, we might feel as though the Navy’s shipbuilding problems are more pertinent than NASA’s rockets, but in 50 years, we might look back at ceding the Moon to China as our nation’s greatest strategic blunder.

We may not know for sure, but Sandboxx News will be rooting for the astronauts aboard the first crewed Artemis launch this coming February.

Feature Image: Chinese news rendering of China’s Beidou satellite. (Photo by 中国新闻社/Wikimedia Commons)

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Heroism of The Hulk: A SEAL in Vietnam demonstrated the true meaning of valor

- Delta man’s showdown against a bully at Wendy’s

- The A-12 Avenger II would’ve been America’s first real ‘stealth fighter’

- Could Turkey be accepted back into the F-35 program?

- America’s 70-year-old B-52 bomber now has a radar better than most of Russia’s fighters