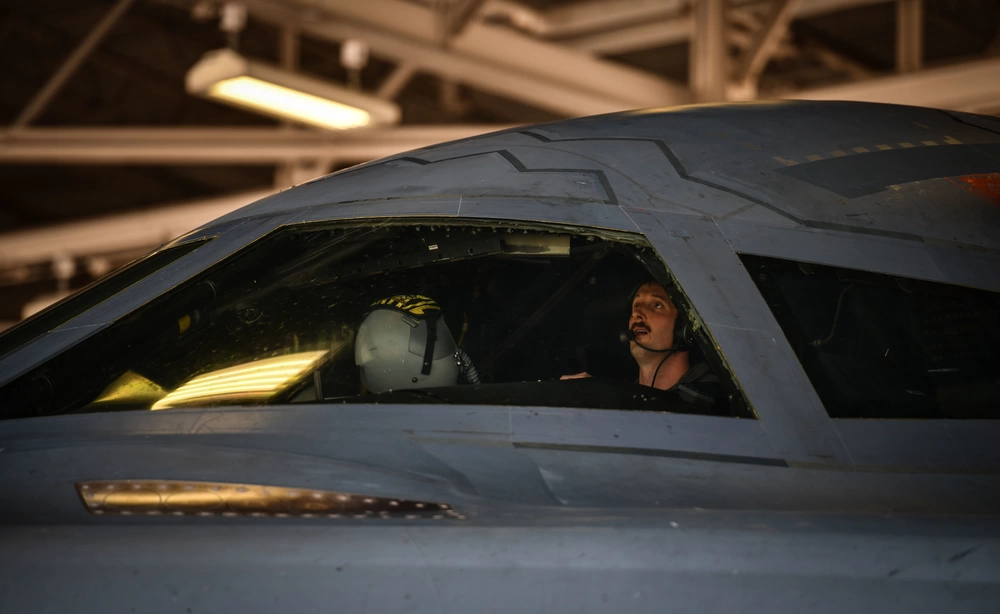

The B-21 Raider, touted as the world’s most technologically advanced strategic bomber, is expected to conduct globe-spanning missions that could last upwards of 40 hours. And yet, according to a recent Air Force Global Strike Command memo, the B-21 may be the first American heavy payload bomber in history to fly these marathon missions with just a single human pilot onboard, instead, the second cockpit seat will be reserved for a weapons systems officer (WSO).

“Unleashing the Raider’s full potential demands a complex blend of skills: airmanship, weaponeering, electromagnetic spectrum operations, sensor management, real-time battle management and agile replanning in combat. For this reason, the B-21 will be crewed by one pilot and one weapon systems officer,” a recent memo from General Thomas Bussiere, the Commander of Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC) said.

This memo represents Global Strike Command’s recommendation, and isn’t official yet.

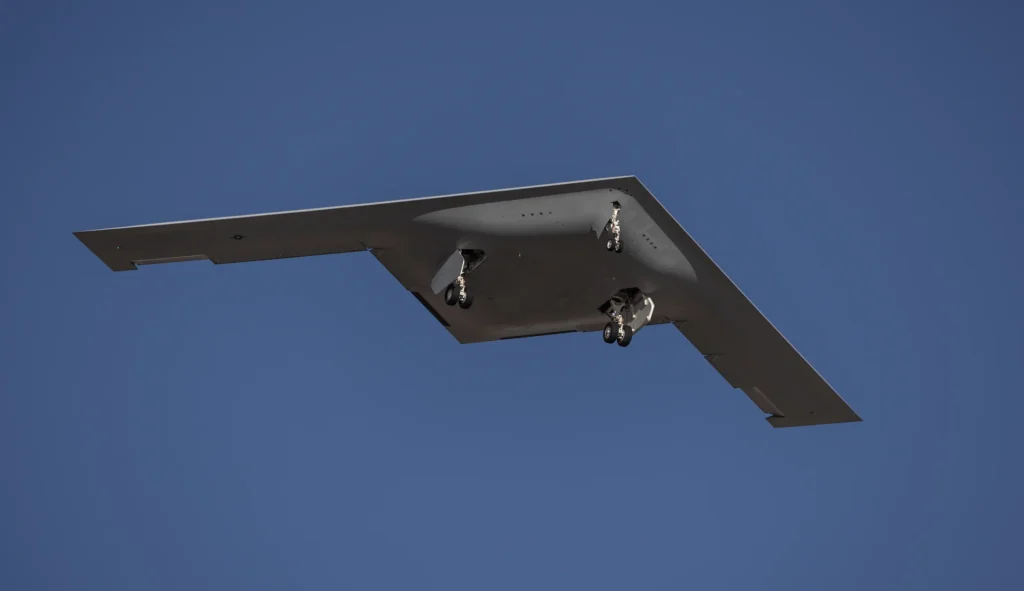

Today’s B-52s and B-1B Lancer bombers operate with a pair of pilots and weapon systems officers onboard. Even the advanced B-2 Spirit, the B-21’s direct stealth predecessor, flies with two highly trained pilots who use automation and thorough planning to distribute mission responsibilities.

Many of the roles previously divvied up among flight engineers, navigators, bombardiers, and more have been streamlined and automated into little more than auxiliary duties for the two pilots, who meticulously schedule their missions to ensure both are awake and alert when necessary, while also allowing opportunities for rest in the meantime. In particular, both pilots need to be alert and in their seats not just for the weapons engagement portion of the flight, but also for each and every complex and risky mid-flight refueling, which, depending on payload, may be as frequent as every few hours.

“When you’re faced with a 24-hour mission, or a long-duration mission, you really get into the details of who is going to do what task, and how we’re going to manage our sleep. The timing of every task needs to be set in advance “so that we’re both prepared to be in the seat, ready to go, for all the air-refueling and the weapons activity, and then of course landing,” Lt. Col. Niki “Rogue” Polidor, a B-2 pilot and the 509th Bomber Wing’s chief of safety, said in 2019.

But just because there’s time to rest it doesn’t necessarily mean anyone gets to. Because of the duration of these missions, target coordinates often change after the bomber has already departed, which not only means needing to feed new coordinates into targeting computers and each individual precision-guided weapon, but often requires changing or planning entirely new routes to those new target sets.

“You’re reviewing target folders, reviewing timing, checking our fuel consumption so that we’re not going to run out of gas over the Pacific,” retired Air Force Col. Mel Deaile, who flew a record-setting 44.3 hour B-2 bombing run back in October 2001, has said.

In these conditions, it isn’t uncommon for sleep to be intermittent or impossible for long stretches of the flight, so pilots have often been issued “go-pills” by flight surgeons to help keep them awake when they need to be.

Put simply, with such a significant pilot workload, it’s hard to imagine a world where these kinds of globe-spanning bomber runs could be done with anything less than two pilots onboard.

So, Air Force Global Strike Command’s revelation also points to an ever more groundbreaking change to combat flight operations: a bomber with such advanced onboard autonomy that the role of the pilot will shift away from actually flying the plane, and toward supervising an AI co-pilot instead.

An important effort is being made to change the way crewed aircraft operate. For example, next-generation fighters like Boeing’s F-47 are being designed from the ground up to fly at the center of a constellation of drone wingmen ranging in cost and capability from single-use systems that blur the lines between drones and missiles all the way up to fully-fledged and pilot-less multi-role stealth fighters.

Related: Boeing makes a significant step toward fielding truly combat-capable drone wingmen

This wide variety of pilot-less assets, each offering different combat capabilities and thresholds for acceptable risk, means the pilots at the heart of these formations will really have their work cut out for them: they will not only be flying their own few hundred million dollars worth of state secrets through fiercely contested territory, but providing command instructions to anywhere from two to maybe as many as dozens of drones throughout the battlespace. This promises to place an immense cognitive load on fighter pilots who were arguably already over-tasked in the heat of the fight.

The Air Force is following several approaches to new system development in order to combat this information and sensory overload.

The first is finding the right way to manage drone assets, which means finding the right pilot-drone interface. (Currently, evidence is pointing toward using a tablet mounted in the cockpit or on a knee-board, but other control methods, like giving simple voice commands, are also being explored). The second is giving the drones themselves the edge-computing capabilities they need to turn simple commands into complex actions without needing to be micro-managed by the human pilot. “Edge-computing” means having the processing power necessary onboard the drone itself to operate effectively with intermittent or interrupted communications with the fighter they take their cues from.

Yet, a lesser-discussed approach is all about installing an advanced AI co-pilot directly into the cockpits, effectively allowing artificial intelligence to handle the more mundane aspects of flying while the pilot serves as more of a battle manager than a traditional stick jockey.

You might compare this new approach to an offensive coordinator in the sky – with more sensors, more data, and more assets to manage, but perhaps a bit further removed from our traditional idea of fighter pilots pulling off crazy maneuvers and firing all the missiles themselves.

The B-21 has been touted since its onset as an optionally manned bomber platform, and that, combined with the Global Strike Command’s recommendation that the aircraft fly with just a single pilot onboard, points toward the Raider being among the first military aircraft to fully embrace this idea of an advanced AI copilot, which is distinct from the idea of autopilot as we see in many commercial aircraft today.

Modern autopilot systems are integrated into an aircraft’s Flight Management System (FMS) and navigation suite, and they are capable of managing most aspects of a run-of-the-mill flight between airports. In fact, the more modern autopilot systems can really do everything except taxiing down the runway and taking off; they can manage heading and throttle inputs more or less automatically throughout the ascent, cruise, descent, approach, and even landing phases of the flight. But as handy as these systems are, they’re also very limited and effectively capable of doing only what the pilot has programmed them to do. If the circumstances of the flight change, if the course needs to be adjusted, if there’s another aircraft to avoid, etc, the pilot is alerted and will need to either take control of the aircraft or adjust the program settings of the autopilot to accommodate that change.

An advanced AI copilot, on the other hand, rather than relying on pre-programmed directives provided by the pilot, would soak up data from the same wide variety of sensors the human operator uses to make their decisions. If a threat presents itself, like being lit up by a radar array tied to a surface-to-air missile system, an AI co-pilot could deploy RF countermeasures and take evasive action, potentially even faster than a human pilot might. If new threats appear on the battlefield that weren’t there during mission planning, an AI co-pilot could rapidly calculate the new best possible route through contested airspace to minimize detection, notifying the pilot as it adjusts course. This AI co-pilot may be every bit as good as a human operator at most run-of-the-mill operations and even some more complex ones, leaving the actual pilot to serve primarily as a supervisor, only needing to take direct control of the aircraft for the most dangerous or complex parts of a mission.

Related: The Air Force is now adding AI pilots to combat-coded F-16s

In extended-duration bomber operations, this would mean the human pilot could rely on the aircraft’s AI co-pilot to handle basic flight functions while they get some rest between mid-flight refuelings. Further, it would eventually mean being able to fly less complex strike operations without any human operators onboard at all.

As for the weapons systems officer, their responsibilities could vary from: managing mission-specific hardware for electronic warfare or radio-frequency countermeasures; employing weapon systems that there’s at least some evidence to suggest could include the bomber’s own air-to-air missiles; soaking up signal intelligence; identifying targets; conducting immediate battle damage assessments; and managing any drone wingmen the bomber may have flying alongside it. And much like the WSO’s found in today’s F-15E Strike Eagles, they’d all but certainly receive training in how to fly the aircraft themselves, in the event the pilot is incapacitated.

And, of course, for particularly grueling and stressful long-haul bombing runs, that WSO could just as easily be swapped out for a second pilot to make rest breaks more feasible.

Global Strike Command’s intent of making the B-21’s standard crew makeup one pilot and one weapons systems officer makes perfect sense in the broader scope of America’s rapid progress toward using artificial intelligence to manage flight duties in drones and fighters.

In fact, one could argue that reducing the number of pilots in strategic bombers points toward America’s growing confidence in its AI piloting systems. And if that is indeed the case, then we would expect to see more aircraft follow the Raider’s lead in the not-too-distant future. If these AI agents are capable of flying fighters and bombers, then they’ll all but certainly be reducing crew requirements for less arduous missions, like cargo operations, just as soon as the control hardware becomes cost-effective to install across the fleet.

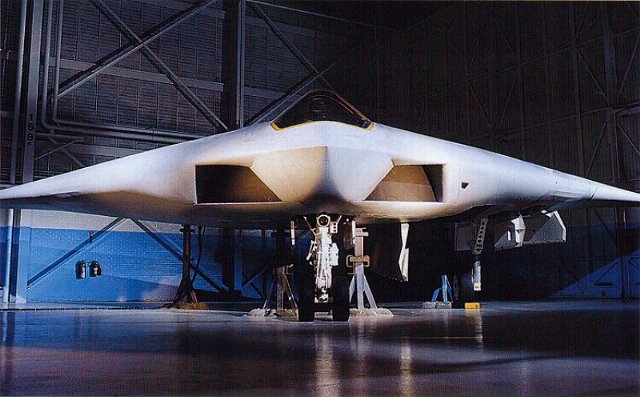

Feature Image: Northrop Grumman’s B-21 Raider. (U.S. Air Force)

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Russia has built an enormous 500-drone air base to attack Ukraine, investigators reveal

- Russian suicide drone attacks increase by 303% in a year

- How B-2 crews relieve themselves during globe-spanning missions

- HMS Prince of Wales aircraft carrier reaches full operating capability

- The US military looks to bring GPS back up to the global standard