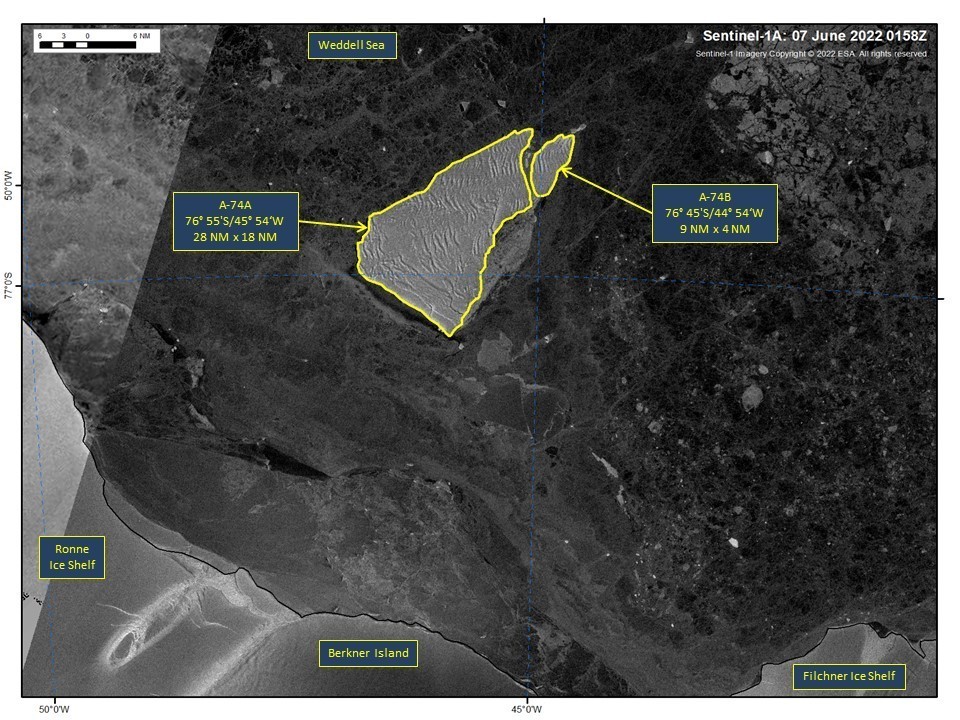

Navy civilian and master icy analyst Katherine Quinn was doing a weekly check-in on the icebergs she monitors when she saw it: a tooth-shaped hunk that had split off from iceberg A-74 in Antarctica’s Weddell Sea. The iceberg had “calved” or split into two drifting pieces, each as large as a major world city.

A-74A, as it was now called, the biggest piece, measured 28 nautical miles by 18 nautical miles, or about 32 by 21 land miles. A-74B, the calf, measured nine nautical miles by four nautical miles, or about 10 by five land miles – as long as Washington, DC, and about half as wide.

But why does the U.S. military care enough about how ice splinters at the bottom of the globe to have an office dedicated to tracking it?

The National Ice Center

It turns out that the U.S. National Ice Center, run by U.S. Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command, based in Suitland, Maryland, and staffed jointly by active-duty officers and civilians from the Navy, Coast Guard, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is the only entity that monitors ice movement and formation across the globe. And it has been doing so since shortly after World War II when the Navy began monitoring ice for its own ships.

The most famous ship vs. ice catastrophe is, of course, the sinking of the RMS Titanic on April 15, 1912, but the Navy had plenty of opportunities to consider the value of reliable tactical ice monitoring as it operated in the icy waters of the North Atlantic. The service even hatched a plan to install a flight deck on an iceberg and turn it into an aircraft carrier, building a prototype out of an ice-sawdust blend called Pykrete in Canada’s Patricia Lake in 1943. Sadly, that science fiction-esque carrier never made it to the fleet.

Today, lots of different entities may want to stay abreast of iceberg calving and other ice movements Katherine Quinn told Sandboxx News in a phone interview.

“Calving is a natural process, so it’s going to happen. A lot of the ones that we do track are very large. And if a ship is down there, they can see it,” she said. “I know researchers [also] use that information. There are companies, there are scientists tracking that information.”

Fast and dangerous

Not only are the icebergs that the center tracks huge – they are now monitoring 53 bergs in Antarctica that are at least 10 nautical miles across – but they can move pretty fast too. A-74 became an iceberg when it calved from the Brunt Ice Shelf, home to the British Antarctic Survey’s (BAS) Halley Research Station, in March 2021. It has since drifted 90 nautical miles – or 104 land miles, westward, officials at the National Ice center said.

The researchers at Halley had been tracking the potential calving event for 10 years or more, relocating one of its research stations in 2016 and limiting deployments to the station to the Antarctic summer in 2017 in recognition of the upcoming need for a sudden evacuation.

In August 2021, the newly formed A-74 was hit by strong easterly winds and collided with the shelf, a largely non-event, but one that could have created a new, massive berg if the collision had happened with more force.

National Ice Center analysts to go

Coast Guard cutters and Navy surface ships and submarines often check in with the National Ice Center ahead of deployments or planned movements to get an accurate ice picture of their destination, Quinn said.

“We actually do provide tailored support products. So if a ship, whether it’s Coast Guard, or a Navy ship, or research ship, universities, all of that – when they are traveling somewhere, they could say, ‘Hey, this is where we’re going. What can you provide us?'”

In addition to tracking current ice formation and forecasting future ice, analysts from the center sometimes deploy aboard Coast Guard icebreakers to conduct research and provide the crews with an extra level of situational awareness.

Quinn added that the center produces a daily ice analysis, which shows ice coverage and distinguishes between light ice and pack ice, new ice formation, and old ice, so skippers know exactly what they’ll encounter in a new region.

To do that, Quinn and the other analysts rely on tools including incredibly detailed satellite imagery from NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) and NOAA’s Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS). They also use synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery, which uses radio waves to create three-dimensional models of landscapes and other objects. When clouds or harsh weather patterns obscure an area, Quinn said, SAR imagery can still provide an accurate ice picture. But there are certain things only a practiced human eye can pick up.

New ice, she said, doesn’t show up on the visible imagery, and thus must be interpreted from the SAR models.

“For the new ice, it’s going to be darker and you’re going to see it forming around the current ice edge,” she said. “As it thickens up, it turns brighter … As ice grows it will start to fracture, so the new ice becomes young ice. As that ice is circling around the Arctic for a season, or multi-year ice, those floes become more rounded and also darker. So we know what type of ice we’re looking at based on appearance.”

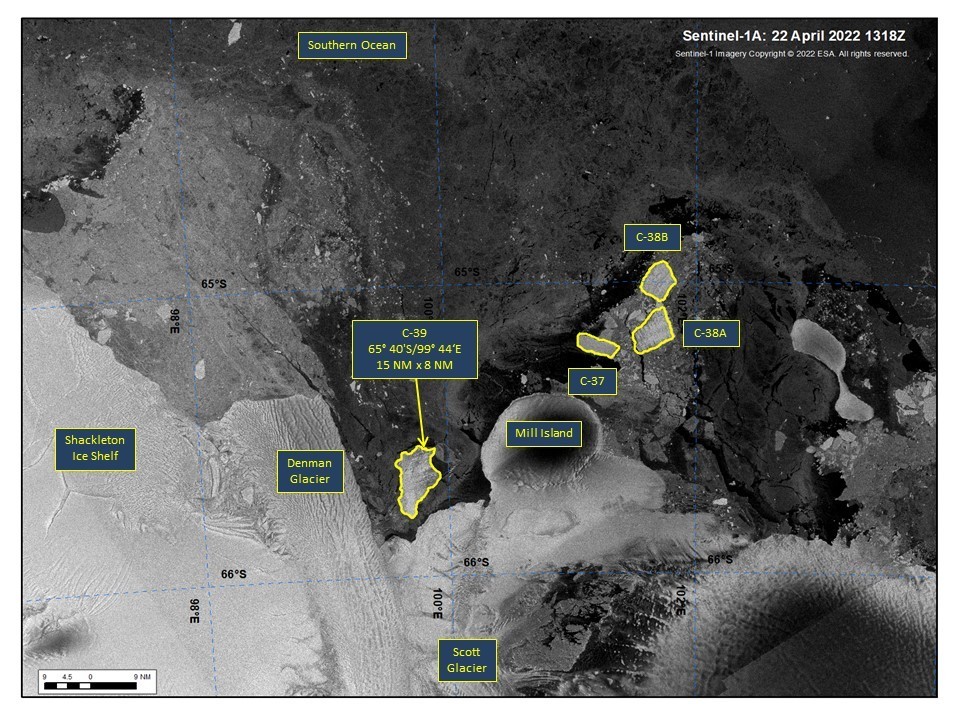

Erratic like ice

Calving can be frenetic at times, sporadic at others. Before A-74’s calving in June, the last announced calving was the creation of a new iceberg, C-39, from the Scott Glacier area of the Shackleton Ice Shelf in April. Icebergs are named based on the quadrant in which they were formed (A, B, C, or D) and then the order in which their tracking by the Ice Center began. The center does not name Arctic icebergs, which are generally much smaller than their southern counterparts.

“I was off for a few months a couple years ago, and when I came back, there was a ton of new bergs,” Quinn said. “Sometimes they’re just constantly calving and breaking.”

While Quinn said she didn’t want to comment on trends in ice activity or how it has been affected by climate change, saying she wasn’t a climatologist, scientists have said that warmer Antarctic air and ocean temperatures have led to increased ice shelf collapse. (The calving of A-74 from the Brunt Ice Shelf was not believed to be climate change-related.) Top Navy and Coast Guard officials have spoken repeatedly about how newly opened sea routes in the Arctic are changing the national security picture and creating a new global competition for dominance.

“Our work is and always has been important. And I think we’re also increasing our customers because of what we do and the services that we provide,” Quinn told Sandboxx News. “Our active-duty officers who are here, they’re learning what we do, and they’re taking that with them to their new commands. And they’re telling us, they’re telling these commands, ‘Hey, if you need ice analysis, the National Ice Center’s got it for you.'”

Read more from Sandboxx News

- The Army is pushing the limits of bridging ops as Ukraine’s fight spotlights river crossings

- The Army wants to use oil-eating enzymes to power its electric vehicles

- Why peace in Ukraine is unlikely anytime soon

- Watch: American HIMARS missiles destroy Russian-occupied bridge

- DARPA’s new missile hints at truly game-changing technology