Editor’s Note: Sandboxx News presents a World War II series by Kaitlin Oster on the power of hope, letters, and love in seeing us through the terrors and agony of war. You can listen to Kaitlin’s radio interview about the series here or visit her website here.

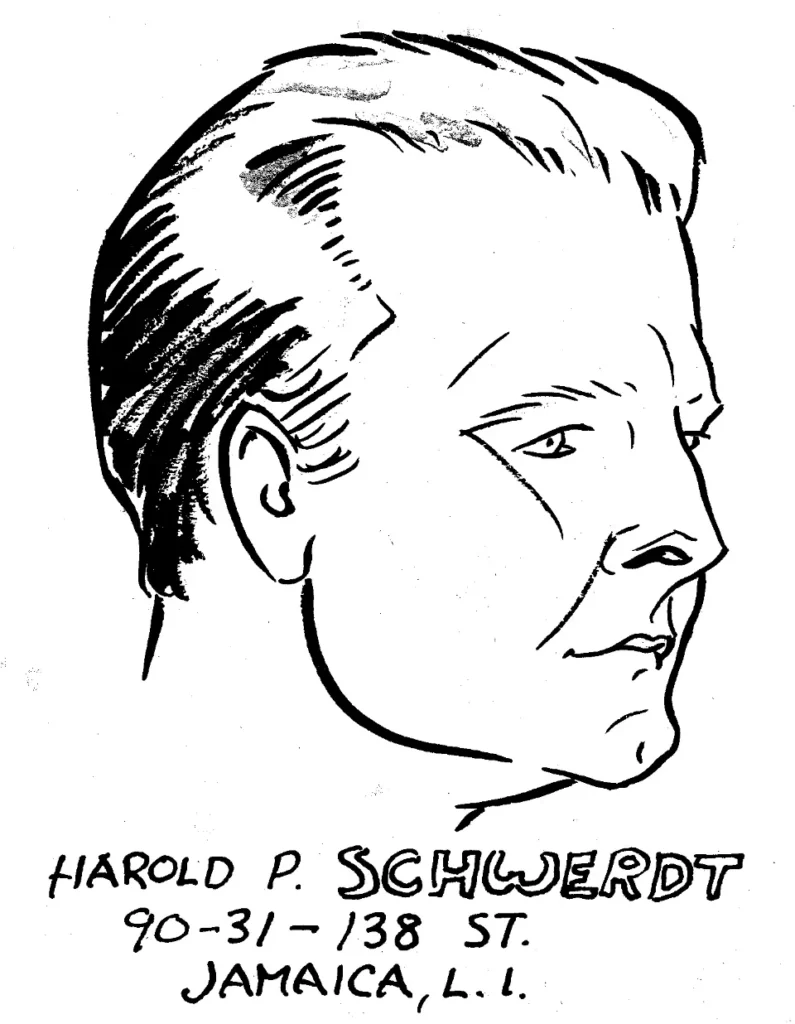

Loretta died on December 24, 2007, at eight in the morning. It was her third fight with breast cancer, but this time around it metastasized throughout her entire body. She was 85 years old. Her last birthday was spent at the local diner with Harold. She ordered an English muffin, “extra crispy, plenty of butter.”

Looking at her, you wouldn’t know she was dying. Her old radiation scars on her left breast had opened up and would never heal again, so Harold made it his duty to clean her wounds each day. Keep it dry, prevent infection, keep her comfortable. They led a comfortable life before the diagnosis – the one Harold had promised in his letters. A small cottage on the water, a couple of kids, grandkids, boats, and summer rain on the creek. On her last Thanksgiving, the family brought hats to dinner to wear at the table in solidarity with her missing hair. Her final meal was pound cake and strawberry ice cream. She died at home, in her own bed, surrounded by loved ones. It was quiet and peaceful on an uncommonly warm Christmas Eve morning.

Harold maintained to live his life purposefully following the death of Loretta. He kept his house clean, welcomed anyone to join him, and slept beside a pillow that was placed lengthwise under the covers next to him. He visited her grave frequently and often joked about how it was unfair for him that she got to be buried in the military cemetery first.

“I did all the work, you know, and she gets to be front and center!”

Related: Letters to Loretta: I Love you. Do you love me?

Harold always speculated he would go immediately after Loretta – and honestly so did the rest of the family. They had spent so long together before her passing it seemed abnormal and unfair for him to have to walk the earth alone without her. And he marched on, that military man. He woke up grateful every day even though she was no longer there to greet him. He drank bourbon Manhattans in her memory (and for his own enjoyment, honestly). Harold participated in Bingo every Tuesday at the local Legion Hall until 2014 when he simply could no longer keep up with the math and his arthritis affected his handwriting.

At almost a hundred, Harold could afford to drag his house slippers once in a while. If he had a busy day, though, he would stir under the covers, the still-dark windows ready to welcome first light.

“I need to eat early,” he said, before he took his after-breakfast nap, the one that predated his weekly bowling club.

“Thank you, Jesus, thank you, Mary,” he mumbled as he turned over and slipped out of bed. Since 1945, he laid claim to the right side, Loretta always on the left. A simple blue blanket, scratchy to most, was all he needed. He never tucked it under the foot of the bed because he didn’t like to feel trapped. He sat up on his side, nightmares already forgotten, and rubbed his cataract-blurred eyes, glad to not see too much anymore. His body slowly adjusted to the morning.

As light crept up over the creek and the garden, he would sigh his remaining breaths of the night before. The cottage stretched in the light and shadows formed in little, forgotten corners. It was another day to himself and there was no one or nowhere to rush to just yet. The house breathed with Harold; if walls could talk, they’d tell him to take his time.

“Let the blood find its way to my feet.” He always grunted as he staggered upwards, clad only in his underpants. Deep, long scars – history – covered his back and belly. He carefully pulled the itchy blanket back up so as to not disturb the pillow that kept Loretta’s place for the last 11 years since her passing.

Related: The ‘shadow scheme’ Britain used to disperse WWII production

Harold cherished fried egg day. I didn’t know why until he told me about the night he traded needles for one. Then, it made sense, how patient he always was with his scrambled eggs while my brother and I – small children at the time – drooled over the pan, begging him to cook them faster.

So much innocence and simplicity existed for him in his old age, that it was difficult to believe his life was once riddled with agony, without sugar packets and real coffee, without anyone he loved. Everything around him became itemized and regimented, not just because he had become an old man, but to ensure that he was never left wanting for the essentials. And all Harold needed was a sweetener in his coffee, eggs in the fridge, and love from his wife.

He recited a rosary and rocked in one of two matching recliners. Each prayer passed between stiff but delicate fingers before he placed the beads back on the end table he made in 1938. He rubbed his hands together to loosen up the tendons where arthritis had taken over, and felt his missing pinky finger, something he hadn’t seen since 1943. Harold lingered over the space where a gold band rested for almost 70 years. Phantom limbs and phantom love.

At night, even when Loretta slept beside him, Harold would always find himself back behind the wire fences of the Nazi POW camp. He could still hear the guard dogs bark, and people scream for their lives, and watched as the watchtower lamp circled him, making sure every last man was still in his place. Each night, Harold felt himself falling faster and faster toward the ground, blood filling his bomber jacket, head spinning. He saw the faces of scared villagers, sad children, and merciless German soldiers. He dreamed of – or remembered – the nights, the gunshots, the hunger. And when Harold would eventually wake up, he would first see the ceiling of his own home, and next the beautiful face of his wife, who understood.

Related: How to keep your military family feeling close during deployment

Harold found himself able to separate the nightmares from the present for over half a century. It wasn’t until his 90s that he noticed a blur between the two. A bug bite caused him to flip his bed over and buy new linens. A dream of being chased by German Shepherds had him soil himself in his sleep. He didn’t mind all too much – said he didn’t – because at least when he woke up he was home in New York and not in Stalag 17B. He could calmly walk across to the bathroom and soak his underwear, change his sheets with one of several choices, replace the blankets, and freely take care of his day.

He missed Loretta, but part of him enjoyed the solitude, he admitted. I know Harold would have given anything to have his wife with him again, or at least to have died beside her in 2007, but he understood that he still had business to take care of, and was grateful that his home was shared with his daughter’s urn, his visiting family, and the occasional spider. Harold never was much of a talker, although he loved writing letters. He gained even more of an appreciation of silence in his older years. No clinking of tin cups to be heard – no losing tin cups for that matter. No three men to one bunk in a long, dark room, but windows that invited sunshine and provided views of his flowers. Everything was simple and he liked to keep it that way.

In his simplicity, Harold would drift off from time to time and wonder what exactly he was still doing here.

“I’m almost a hundred, and still going,” he would say. He insisted he was paying penance for the war, or a past life maybe, or for the men he had killed. Those close to him wouldn’t think for a second that he had any penance to pay. He wasn’t sure, though, but he often speculated there had to be some other reason.

When Harold would lay back down to nap, he didn’t bother to set an alarm. He never set an alarm toward the end. Partly because his internal clock was so regimented, and partly because if he died in his sleep he didn’t want to have an alarm going off until someone found him. Harold decided long ago that he wanted to die at home, just like Loretta did that one Christmas Eve morning.

Related: Letters to Loretta: A series into the power of humanity to persevere during war

“I’m the last of the Mohicans,” he mentioned as he left his best friend’s funeral. It was 2018.

“He lived to be a hundred! By the way, I want this song at my funeral, too.” Harold pointed to the pamphlet he took from the church. I had to roll my eyes and try not to laugh at how loose he was with mortality.

“I’ll make a note of it but it isn’t your party, Pop. It’s Troy’s,” I replied.

“Party, alright!” He laughed in the middle of church.

There was a lingering sadness somewhere behind his eyes, but they were still the brightest blue. Bright and deep like his love for my grandmother. It was what helped him survive prison camp – that and the letters. A large shoebox filled to the brim; letters that I painstakingly organized in chronological order, then read, and read again while seated in my office at home. He didn’t remember I had the letters; I didn’t even think he knew they still existed.

My grandfather didn’t divulge his stories in a consistent order, and more often than not he tried to remain quiet about his experiences. Some days, he recounted with vigor a memory with his friend Jack. On other days he choked back tears as he recalled his helplessness when watching another man die. The worst was when he described the sounds of metal shredding metal, of the air sucked out of his lungs as he fell out of the sky in the B-17.

I listened and wrote, or remembered, and wrote as soon as I could. Harold represented a dying breed of man, the end of an era, the last of the Mohicans. His story was plotted across two oceans, several states, and deep in the belly of German territory – a place he went so often in his sleep at night; he almost always refused to revisit it when he was awake.

Amid the horrors, he found a silver lining in his stories of Loretta. He talked about Jamaica, Queens, the train station, and giving her a kiss in between work shifts. He smiled when he recounted all the times she had stood on the platform to greet him from work or to watch him go off to wherever the Army called. He called her “my girl,” and it was the memory of her that kept his war-torn eyes the brightest blue. All the letters, all the waiting is what gave them their 70 years together; it was what always kept them going.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- How F-16s will make Ukraine’s radar-hunting missiles much more capable

- Why stealth helicopters are so hard to design

- Destroying Kerch Bridge is key to retaking Crimea, but can Ukraine manage that?

- Sandboxx’s Alex Hollings nominated for 5 Defence Media Awards

- The Soviet version of Operation Paperclip was way bigger (but less successful)