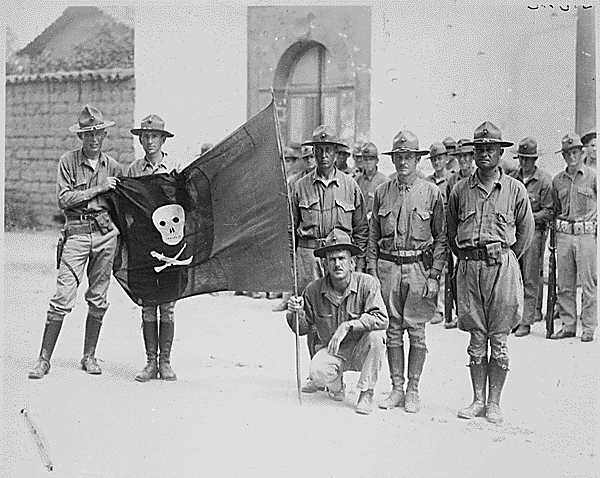

Every military branch, community, or unit takes great pride in its history and the men and women who shaped it. There are few better ways to build esprit de corps than by immersing a freshly arrived troop or candidate in the history of the unit. Some communities and units have more history than they can use, a testament of hard-fought actions or heroics from past legends. For others, which might be newer or less fortunate in the eyes of fate, the actions of one or two troops may serve to define the whole community.

Established in 1946 and often attached to other special operations units, the Air Force Pararescue community falls under the latter category. And it was the actions of Airman 1st Class William H. “Bill” Pitsenbarger and his dedication to the Pararescue creed “So That Others May Live” that defined what it means to be a PJ.

Combat Search and Rescue

Pitsenbarger was born on July 8, 1944, just shy of a month after the invasion of Normandy, in Piqua, Ohio. When he reached his senior year in high school, Pitsenbarger pleaded with his parents to let him drop out of school and join the Army Special Forces. Like all sensible parents, they prohibited it, forcing Pitsenbarger to enlist upon graduation in the Air Force, thanks to its less dangerous lifestyle. But after boot camp, Pitsenbarger’s was still intent to find his way into special operations, and he volunteered for the Pararescue pipeline.

Related: WOMEN READY TO MAKE HISTORY IN AIR FORCE SPECIAL OPERATIONS

Pararescue has one of the longest and most arduous special operations pipelines in the U.S. military, lasting approximately two years. Nowadays, after a tough selection process, candidates go through a succession of schools, such as combat diver, military freefall, Survival, Escape, Resistance, and Evasion (SERE), and emergency medicine, before graduating and getting assigned to either a special tactics or rescue squadron. When Pitsenbarger went through training in the 1960s, the pipeline was similarly challenging.

Upon becoming a PJ, Pitsenbarger volunteered for service in Vietnam. There, Air Force rescue squadrons saved downed pilots and wounded troops on a daily basis. And as the war flared up, the opportunity to see action was almost guaranteed. That is what Pitsenbarger knowingly volunteered for.

What made these Air Force rescue units essential was their unique capabilities. The Army and Marine Corps mainly flew the UH-1 Hueys or larger CH-53 Sea Stallion and CH-47 Chinook helicopters. Despite their benefits, these choppers were limited when conducting operations over the thick, triple-canopy jungle, which often reached 150 feet, like the one found in a lot of places in Vietnam.

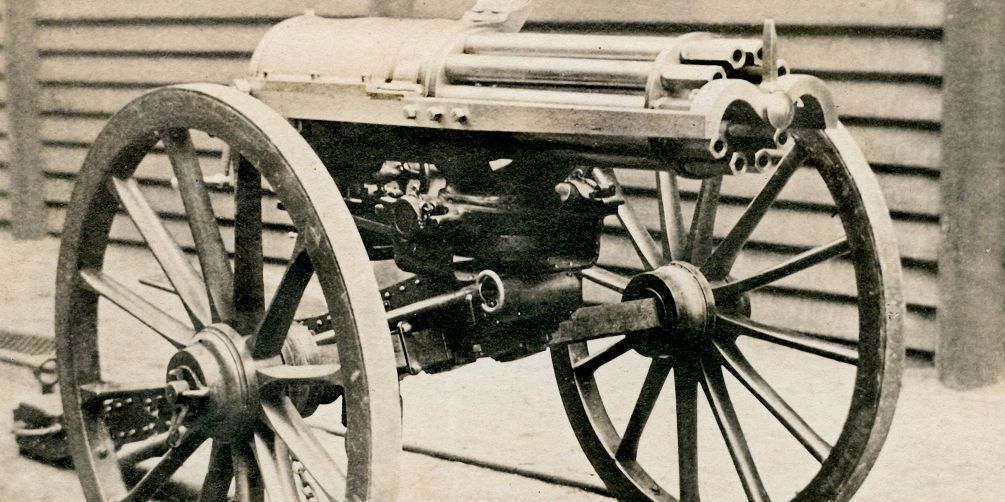

The Army and Marines needed clearings to land and off-load or load troops. So, when it came to combat search-and-rescue, where landing a chopper was often out of the question, the Army and Marines came up short. But the Air Force’s HH-43 Huskie and later HH-3 Jolly Green helicopters could hoist wounded troops out of even from the thickest jungle, thanks to its specialized cables, winches, and stretchers.

The HH-43 was the first dedicated combat search-and-rescue chopper to arrive in Southeast Asia, and also the last to leave. Between 1966 and 1970, Air Force rescue squadrons flying the HH-43 conducted 888 successful combat search-and-rescue missions, saving 343 downed aircrews and 545 ground troops.

Related: The LEGENDARY VIETNAM SPECIAL OPERATIONS UNIT YOU’VE NEVER HEARD OF

Once in Vietnam, Pitsenbarger showcased his bravery and dedication to the Pararescue creed. One time, his unit was called to rescue a South Vietnamese soldier who had unwittingly entered a minefield and stepped on a mine, losing his foot.

The South Vietnamese soldier couldn’t move, let alone crawl back to safety lest he triggered any more mines. But every minute he stayed there he came closer to death. Once Pitsenbarger’s helicopter reached the scene, he volunteered to be hoisted down onto the minefield to strap the wounded soldier onto a litter, disregarding the danger stemming from the HH-43’s powerful rotor wash that could potentially detonate the mines below him.

Pitsenbarger was successful, and his initiative and bravery saved the South Vietnamese troop from certain death.

William Pitsenbarger: Living the Creed

April 11, 1966.

The approximately 144 soldiers of Charlie Company, 2nd Battalion, 16th Infantry Brigade, 1st Infantry Division, found themselves surrounded by a Vietcong force five times their size in thick jungle some 35 miles east of Saigon, the South Vietnamese capital.

The U.S. troops had been ambushed and pinned down by the North Vietnamese guerillas. Despite the disadvantage, American troops held their lines, exchanging fire for hours. As the battle went on, however, casualties began to mount.

Nearby, the Air Force’s 38th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron (38th ARRS) was on standby for any combat search and rescue missions in the vicinity. Pitsenbarger was assigned to the 38th ARRS’ Detachment 6 as a rescue and survival specialist, and when Charlie Company called in for urgent medical evacuations, it was Pitsenbarger and his fellow Airmen who got the call.

Two HH-43 Huskie helicopters went in. Pitsenbarger was riding on the second chopper, callsign “Pedro 73.” As the fierce firefight continued on the ground, the two Air Commando crews hoisted litters to get the critically wounded out of there and back to base. The triple-canopy jungle, however, slowed down their work, so Pitsenbarger volunteered to go down to the ground to help expedite the process.

With only a medical bag, M-16 rifle, and sidearm, Pitsenbarger fearlessly descended into the fierce battle. He wouldn’t come up alive.

“So That Others May Live”

Once on the ground, Pitsenbarger provided medical attention to the critically injured infantrymen and organized their evacuation to the hovering helicopters, overseeing nine medevacs in several trips. Pitsenbarger ignored standard operating procedures and refused to be hoisted back up with the wounded.

Then, during the tenth trip, Pedro 73 was seriously damaged from Vietcong ground fire and had to return to base immediately. With his ride out departing, Pitsenbarger once more refused to leave and opted to stay on the ground with his Army brethren to see the approaching night out, offering not only his medical expertise, but another desperately needed man for the fight.

Pitsenbarger was right that they would need all the help they could get. As the night pressed on, the intensity of the firefight increased so much that other helicopters were unable to reach the scene. They were on their own.

Related: ST IDAHO: THE SPECIAL FORCES TEAM THAT DISSAPEARED IN THE JUNGLE

The rest of the evening didn’t bring any respite to beleaguered Americans, and the Vietcong pressed on, trying to wipe out the entirety of Charlie Company before it became too dark to execute troop movements. Throughout, Pitsenbarger not only provided vital medical assistance to the wounded, but he also collected and distributed ammunition to the men manning the perimeter defenses, despite having been wounded multiple times himself.

Then, as everyone thought this young Pararescueman to be invincible, an enemy sniper killed him.

Pitsenbarger’s Medal of Honor citation is telling:

“As the battle raged on, he repeatedly exposed himself to enemy fire to care for the wounded, pull them out of the line of fire, and return fire whenever he could, during which time he was wounded three times. Despite his wounds, he valiantly fought on, simultaneously treating as many wounded as possible.

In the vicious fighting that followed, the American forces suffered 80 percent casualties as their perimeter was breached, and Airman Pitsenbarger was fatally wounded. Airman Pitsenbarger exposed himself to almost certain death by staying on the ground, and perished while saving the lives of wounded infantrymen. His bravery and determination exemplify the highest professional standards and traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Air Force.”

Charlie Company survived the night, and the next morning a roll call revealed that they had suffered 80 percent casualties. Pitsenbarger was credited with directly saving nine lives during the initial medevacs and contributing to the survival of a further 60 on the ground.

“There was only one man on the ground that day that would have turned down a ride out of that hellhole—and that man was Pitsenbarger,” said F. David Peters, a veteran of Charlie Company, who was there during the battle.

In June 1966, his grieving parents received a posthumous Air Force Cross, the second-highest award for valor under fire. However, after a fierce battle against bureaucracy, the award was upgraded to the Medal of Honor, which was presented again to his parents in 2000. Pitsenbarger is the first and only Pararescueman to have received the nation’s highest award for bravery.

“Pits is undoubtedly a symbol in the [Pararescue] community. You learn about him and his actions throughout the selection and pipeline—actually, these days—a lot of candidates come in having read something on the man and what he did. For those that make it, Pits’ actions instill a sense of continuity. It’s like, ‘hey, this guy went through the same training and did the same job, and now you’ve got to keep up with that legacy, keep the flag high. There is no better motivation than guts under fire,” a former Pararescueman told Sandboxx News.

Today, the Pararescue community recognizes its best with Pitsenbarger Award, and Pitsenbarger’s story and the fight to get him the Medal of Honor was immortalized by the movie “The Last Full Measure.”

Some communities and units bask in the glory of their forefathers, striving hard to keep up with their sacred legacy, while others treasure their few heroes. To this day, Pitsenbarger and his actions personify what it means to be a Pararescueman and are true to the creed “So That Others May Live.”