In recent days, there’s been a significant uptick in posts about Juneteenth, but because it’s not a part of most history classes, you may have found yourself asking why we celebrate this unusually named holiday.

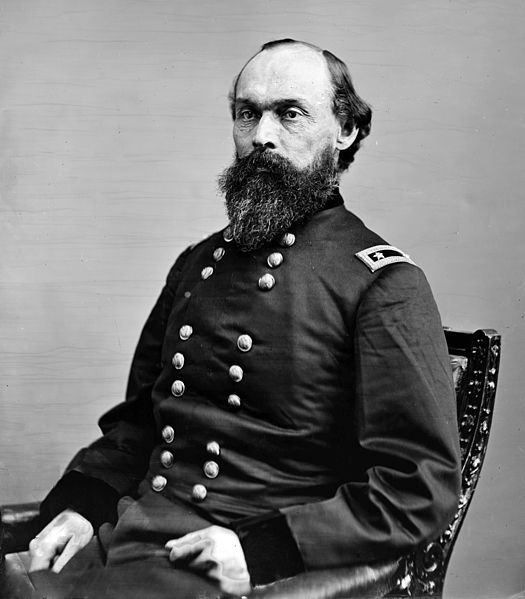

In a nutshell, Juneteenth is a day commemorating the order delivered by Major General Gordon Granger emancipating all slaves in the state of Texas. It’s observed each year on June 19, which is the same day the order was issued back in 1865.

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.

This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.

The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.” — General Orders, Number 3; Headquarters District of Texas, Galveston, June 19, 1865

Slavery was alive and well even after the Civil War in some places

The order, you may have noticed, was issued by General Granger well after the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia had already fallen. Lincoln had already issued his historic emancipation proclamation and had even already been assassinated. So why do we celebrate Juneteenth’s role in ending slavery in the United States if the day itself came well after the blood-soaked battlefields of the Civil War had already gone dry?

Well, it’s because slavery was still alive and well in parts of the nation by June of 1865. This was, in part, because the Union Army couldn’t be in all places at all times, and in part because communications in that era were simply not as quick and efficient as they are today. While the last major battle of the Civil War came and went in April of 1865, the Army of the Trans-Mississippi continued the war throughout May. When they finally surrendered themselves on June 2 of that year, pockets of rebel troops continued to hold out, battling Union soldiers as they spread throughout the newly reunited nation to enforce the Union’s laws.

Related: How a modern battalion of Army Rangers would perform in Civil War combat

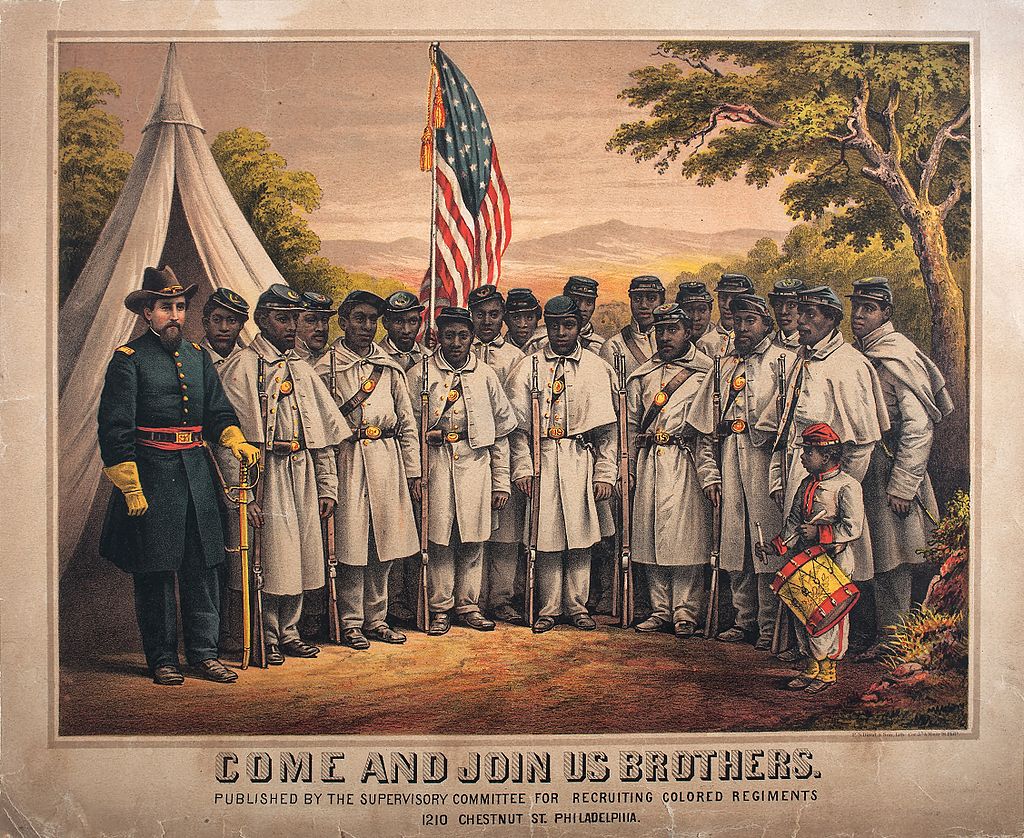

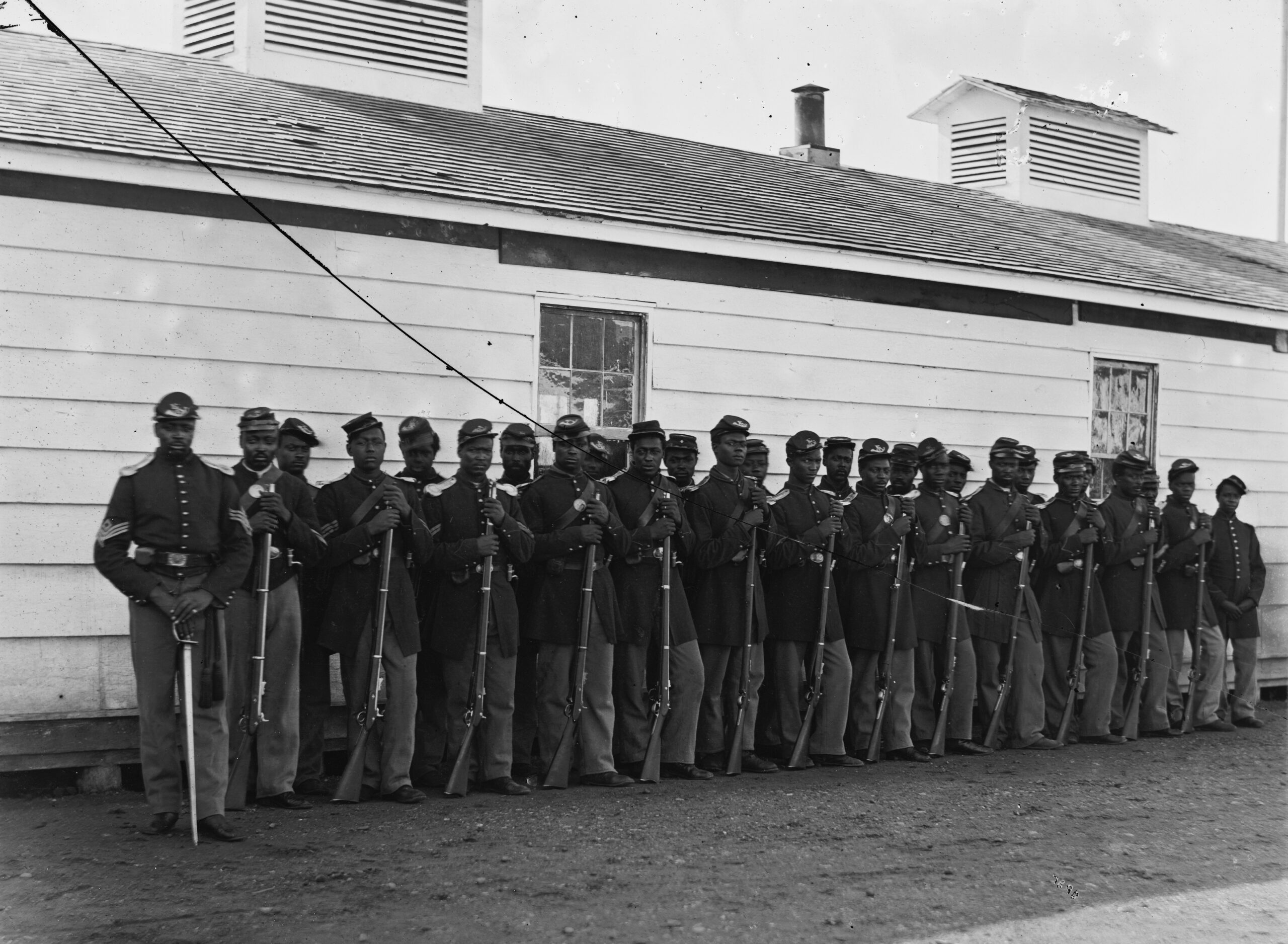

Texas, in particular, had a large population of slave-owning Confederates that weren’t keen to give up their way of life even after their rebel government had fallen. With a concentration of Union troops further east (where the heaviest fighting was), slave owners moved west, hoping to escape the clutches of Union soldiers. When Granger issued his order, it was estimated that as many as 250,000 slaves remained in Texas.

Unfortunately, General Granger and his 1,800 Union soldiers still weren’t enough to enforce his order, and many slaves were hung or shot for attempting to exercise their government-acknowledged freedom. In the case of slave Katie Darling (and many others like her), she would remain a servant to her master for six more years yet.

She “‘whip me after the war just like she did ‘fore,'” Darling said after gaining her freedom years later.

Related: How the American Civil War changed Santa Claus

How the holiday came to be

While the first Juneteenth was hardly a matter to be celebrated (and indeed, General Granger had no idea at the time that his order would become the basis for a holiday), the date itself became a powerful symbol of the freed slave effort, both among freed slaves and within the Freedmen’s Bureau that would be established in September of that same year.

Just one year after Granger’s June 19 order, Juneteenth became a celebrated holiday among those championing the cause of freedom for America’s slaves.

“‘The way it was explained to me,’” one heir to the tradition is quoted in Hayes Turner’s 2007 Juneteenth essay as saying, “‘The 19th of June wasn’t the exact day the Negro was freed. But that’s the day they told them that they was free… And my daddy told me that they whooped and hollered and bored holes in trees with augers and stopped it up with [gun] powder and light and that would be their blast for the celebration.’ ”

Much like today, there was confusion and debate among Americans about celebrating the end of slavery and how best to do it. Some believed America needed to “move on” and stop dwelling on the issue just as the Civil War had ended. By 1885, the movement had gained steam, with people like the Episcopal priest and scholar Alexander Crummell warning against celebrations at all. Others, like famed former slave and civil rights activist Frederick Douglass, championed the cause of celebrating emancipation on January 1 of each year — the anniversary of the date Lincoln’s emancipation proclamation went into law.

Early on, Juneteenth was largely a regional celebration. In 1872, former slaves in the state of Texas collected enough money to purchase 10 acres of land near what is now Houston on which to celebrate Juneteenth annually. Today, that park remains in the Houston area with the apt name, “Emancipation Park.”

Related: 3 black servicemembers who helped shaped history

It wouldn’t be long, however, before newly freed slaves began moving out of Texas to other states around the nation, motivated by new opportunities or chances to reclaim old family members and friendships. As these former slaves spread out from Texas, so too did their Juneteenth celebrations.

However, despite the growing support for the holiday, Reconstruction-era America remained a tensely divided nation, and former Confederate states were not willing to embrace a new holiday based on slaves becoming free. In fact, it wasn’t until 1938, 73 years after the first Juneteenth, that Texas designated it as a day of observance. It’s worth noting that two years prior, more than 200,000 people turned out on the streets of Dallas to celebrate Juneteenth. Still, the day would not become a holiday in Texas until 1980.

It wouldn’t be until the mid-20th century that Juneteenth saw a resurgence in interest among Americans, spurred by the civil rights movement and an increased awareness of the plight of slaves in America thanks to new education programs specifically engaging with the issue.

“The Black Power movement, in particular, with its emphasis on pride, culture, identity, and re-claiming history, helped spark a renewed interest in Juneteenth,” Anthony Greene, an associate professor of African American Studies at the College of Charleston, said in a 2018 essay.

“Additionally, as Black Studies (African American Studies) programs have developed on college campuses, accurate Black historical narratives have emerged, also helping to generate more interest in celebrations such as Juneteenth,” Greene added.

In the years since, all 50 states and the District of Columbia have established some observance of Juneteenth, and efforts continue to have it designated as a national holiday.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published on June 2022. It has been edited for republication.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- The M45 Quadmount – The Krautmower weapon with the devastating power

- The last shots of the American Civil War were fired in Russia

- America’s massive military advantage nobody talks about: 500+ Refueling Aircraft

- Alaska Air National Guard builds houses for Cherokee veterans

- Catherine Leroy: A pioneering war photojournalist