The F-14 Tomcat may be a legendary fighter that got the Hollywood treatment in 1986’s “Top Gun,” but for a short time in the 1970s, the Navy considered tossing the Tomcat in favor of flying the F-15 from its aircraft carriers instead.

Today, the F-14 conjures images of a bygone era, when American airpower was predicated on fielding the fastest, most powerful, and highest-flying jets the nation’s technological capability and economic might could muster. This devotion to brute force and rapidly advancing aviation technology produced incredible platforms that aimed to beat enemy defenses not with stealth, but by straight-up outflying them. Jets like the B-1B Lancer combined the speed and variable-sweep wing design of a fighter with the ability to carry a massive 75,000-pound payload into the fight. Others, like the F-16 Fighting Falcon, emphasized low cost and high performance, becoming the most popular (and common) fighter platform on the globe.

This push for performance was mirrored by America’s Cold War opponent in the Soviet Union. As each nation fielded a more powerful, more capable, or more advanced platform or weapon system, the other would respond in kind, dumping funding into programs aimed at offsetting any potential advantages the other seemed to have. But even amid this era of large defense expenditures and the looming existential threat of nuclear war, budget–as much as capability–often dictated the makeup of America’s arsenal.

And it was just such a debate over dollars and cents that once threatened to put the F-14 on the chopping block, and led to a proposal to field a different kind of F-15 modified specifically for aircraft carrier duty. This new F-15N Sea Eagle aimed to be lighter, faster, more maneuverable, and cheaper than Tom Cruise’s Tomcat, but concerns about armament ultimately kept this jet from ever making it off the drawing board.

But what prompted the Pentagon to consider putting the F-15 on aircraft carriers in the first place? To understand that, you need to understand the failings of the otherwise venerable F-14. Most people are already aware of just how incredibly expensive it was to maintain, but issues with the Tomcat extended well beyond the Navy’s pocketbook.

Related: B-1B Gunship: Boeing’s plan to run big guns on the Lancer

Trouble with the Tomcat

The Grumman F-14 Tomcat was an incredibly capable aircraft, and with good reason. In an era before Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) had matured into the go-to nuclear weapon delivery vehicle they would become, the Tomcat was designed to neuter the Soviet Union’s most potent means of putting nukes on American soil; their long-range bombers. To this specific end, Grumman had designed the largest and heaviest carrier fighter in history, with a fair amount of that weight dedicated to a suite of powerful new weapons and the systems required to leverage them. When fueled up and ready to go, the F-14 weighed in at 61,000 pounds, which is almost twice that of the future F/A-18 and quite a bit more than twice the weight of a fully-fueled F-16 Fighting Falcon.

Despite all of that heft, the Tomcat needed to be fast in order to succeed at its mission, so Grumman paired the F-14 with the TF-30 engines the company had originally fitted to the F-111B they had failed to sell the Navy on earlier. Each engine could produce 14,560 pounds of thrust under military power, with the afterburner kicking output up to 25,100 pounds. All told, the F-14 could use that combined 50,000+ pounds of thrust to push the aircraft to an astonishing Mach 2.3, and its variable-sweep wing design gave it excellent handling at both the low speeds required for carrier landings and the high speeds needed to intercept Ivan before he could deploy his anti-ship missiles toward an American carrier. In fact, those adjustable wings gave the Tomcat a tighter turn radius than most other modern fighters, which can mean all the difference in a dogfight.

But for all its capability, the Tomcat could also be troublesome. The TF-30 engines were indeed powerful, but they were also too sensitive for the job. When operated at high angles of attack, or when the pilot adjusted the throttle position too quickly (both common facets of the air combat the jet was built for), the engines were prone to compressor stalls.

Because the engines were mounted a vast nine feet apart to allow for greater lift and more weapons carriage space, a stall in one engine could throw the aircraft into an often unrecoverable flat spin, ultimately leading to the loss of more than 40 jets.

But it wasn’t just the stall issue plaguing the engine’s in Maverick’s ride. The turbine blades inside the engine were also prone to fail long before their anticipated service life expired, causing catastrophic damage to the engine and putting pilot’s lives at risk. Needless to say, these mechanical issues only made the already expensive F-14 even pricier to keep in service.

Navy Secretary John F. Lehman Jr. went on to say the TF30 engine “in the F14 is probably the worst engine-airplane mismatch we have had in many years. The TF30 engine is just a terrible engine and has accounted for 28.2 percent of all F14 crashes.”

Today, we may look back on the F-14 with wistful awe, remembering how it was the only fighter that could stand toe-to-toe with the (fictional) MiG-28. But when it was in service, not everybody loved the Tomcat… or maybe it’s more fair to say lots of people liked the Tomcat, they just hated its engines.

Related: Vought 1600: The plan to put the F-16 on America’s carriers

An F-15 designed for duty aboard aircraft carriers

McDonnell Douglas could read the writing on the wall before the F-14 even entered operational service. While the Grumman aircraft was plenty powerful and capable, they saw its high cost and mechanical issues as an opportunity to expand production of their own air superiority fighter that was in the works: the yet-to-fly F-15.

Today, we know the F-15 as the most capable air superiority fighter of its generation, with an astonishing 104 air-to-air kills without ever being shot down by another fighter. At the time, however, it was barely more than a paper plane, with its first test flight not to come until midway through the following year. But even if the F-15’s performance figures were technically still imaginary, they were too impressive to ignore.

The F-15’s development had been kicked into high gear the year prior, in 1970, when the Defense Department first got wind of the new Soviet MiG-25 Foxbat. Armed with little more than reconnaissance photos and vague reports of sightings from Israeli pilots, the Pentagon’s experts saw the aircraft’s large wing area and powerful engines as indicative of an air superiority fighter that was unmatched by anything in Uncle Sam’s arsenal. The Air Force and McDonnel Douglas set out to mitigate the perceived advantage the Foxbat provided, redoubling their focus on the F-15s air-to-air prowess. Eventually, the U.S. would learn that the Foxbat was nowhere near the powerhouse they believed it to be, but their misconception had motivated them to produce a very real powerhouse in the Eagle.

The F-15 wasn’t originally designed to serve aboard aircraft carriers, but it was designed to dominate the skies of the Cold War. With the Navy set to begin purchases of Grumman’s pricey F-14, McDonnell Douglas entered a proposal for the F-15N Sea Eagle–and it wasn’t a bad shot.

At a gross weight of 44,500 pounds, the F-15 was 16,500 pounds lighter than the Tomcat with a similar load. That’s the equivalent of an M198 howitzer with a fireteam of troops to run it. Because the F-15 had a relatively low weight-to-wing-area ratio, it was more maneuverable than the F-14, and its less problematic pair of Pratt & Whitney F100-PW-220 engines gave it a higher top speed, beating the Tomcat’s Mach 2.3 by a healthy 150 or so miles per hour.

But better than faster or more maneuverable in the minds of some lawmakers was its price. McDonnell Douglas was prepared to deliver F-15As to the Air Force at a sticker price of $28 million per aircraft (or about $189 million in 2021 dollars). High as that may seem, the larger and more complicated Tomcat rang in at $38 million per aircraft, or about $256 million today. That’s right… one F-14 cost about the same as almost three F-35s today.

Related: F-15 ACTIVE: This Frankenstein fighter was better than the F-15

The F-15N Sea Eagle was the Phoenix missile’s only confirmed kill

In order to make the F-15 suitable for aircraft carriers, McDonnel Douglas knew the platform would have to be modified. The F-15A already had a tailhook, intended for use on short airstrips or in an emergency, but a carrier fighter needs to rely on its hook for every landing, so a larger reinforced hook was added to the design. To make for easier storage below deck on carriers, the wings would fold up at a 90-degree angle a bit more than 15 feet from each tip. The landing gear would also have to be swapped out for a more rugged set that could withstand the abuse of carrier landings on a rocking ship. McDonnell Douglas said they’d set about designing the new gear if the Navy wanted to move forward with the aircraft.

With these changes incorporated, the F-15 only gained a paltry 3,000 pounds, which, combined with better maneuverability, a higher top speed, and a much lower price, all made this new Sea Eagle sound like a pretty good deal… but there was one glaring shortcoming. Capable as the F-15N may have been, it couldn’t carry America’s latest and greatest air-to-air missile, the AIM-54 Pheonix.

The Phoenix missile had been developed for the Navy’s defunct F-111B fleet carrier fighter effort that McDonnel Douglas had also been involved with, so the firm logically migrated it and its supporting systems to their new Tomcat. The AN/AWG-9 radar developed specifically for use with the AIM-54 Phoenix was capable of tracking up to six separate targets at ranges as far as 100 miles. When coupled with a bevy of 13-foot-long Phoenix missiles, it made the F-14 an air-to-air opponent without equal.

In fact, the combination of the Phoenix missile and AN/AWG-9 was so potent, some believed it offset the F-14’s engine woes, arguing that the fighter didn’t need to be fast and maneuverable when it could shoot its enemies down from such long ranges.

Putting the F-15 on America’s aircraft carriers might have been cheaper, and the aircraft itself may even have been better in some respects, but without Phoenix missiles, the Navy just wasn’t interested. However, McDonnell Douglas remained undeterred, enlisting the help of Hughes Aircraft (designers of the AIM-54) and returning to the drawing board to devise a version of their aircraft carrier F-15 that could wield the Pheonix as effectively as the massive but mighty Tomcat.

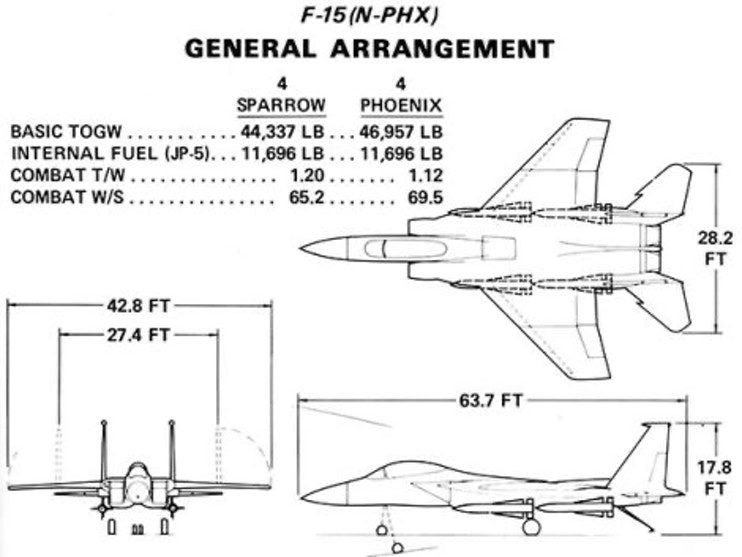

But it wasn’t as simple as slapping these missiles onto the F-15’s existing hardpoints. Not only were the weapons relatively large, but so was the AN/AWG-9 radar needed to run them. The hefty Tomcat could carry a maximum of six Phoenix missiles, but famously couldn’t land with all six still onboard. If ever an F-14 scrambled to intercept Soviet bombers with 6 missiles and returned without firing them, the pilot would have to dump a few into the ocean in order to land safely. Fitting these weapons onto the F-15 was enough work to warrant a new title, and the updated Sea Eagle was dubbed the F-15N-PHX. But with all that added firepower, the new F-15N-PHX weighed in at 10,000 pounds heavier than a standard F-15, totally eliminating its performance advantage over the Tomcat.

In 1973, a Senate subcommittee convened to decide what fighter the Navy would fly into the future, with the F-14, new F-15N, a stripped-down iteration of the F-14, and a heavily upgraded version of the F-4 all considered to varying extents. Senator Thomas Eagleton, who was a Navy veteran himself, proposed a fly-off between the F-15N and the F-14, but it never manifested.

In the end, the U.S. Navy chose to stick with the Tomcat, and surprisingly enough, even the U.S. Air Force found itself looking for a cheaper alternative to the F-15 just a few short years later. Like the Tomcat, the F-15 was incredibly capable, but also rather pricey. The effort to field a lower-cost fighter to complement the F-15 eventually produced the F-16 Fighting Falcon, which the Pentagon would also press for duty aboard aircraft carriers, before the F/A-18 Hornet came about.

The F-15 is far from the only unusual aircraft to be pitched for carrier duty. Make sure to check out our articles about efforts to put the F-16, the F-22, and the F-117 on aircraft carriers, or you can read about how the U.S. really did fly C-130s and even U-2 spy planes off of them during the Cold War.

Want to learn more about the F-15? Check out the Frankenstein F-15 that was better than the one we got here, or how a pilot landed an F-15 after it lost an entire wing here.