This article by Matt Fratus originally appeared on Coffee or Die

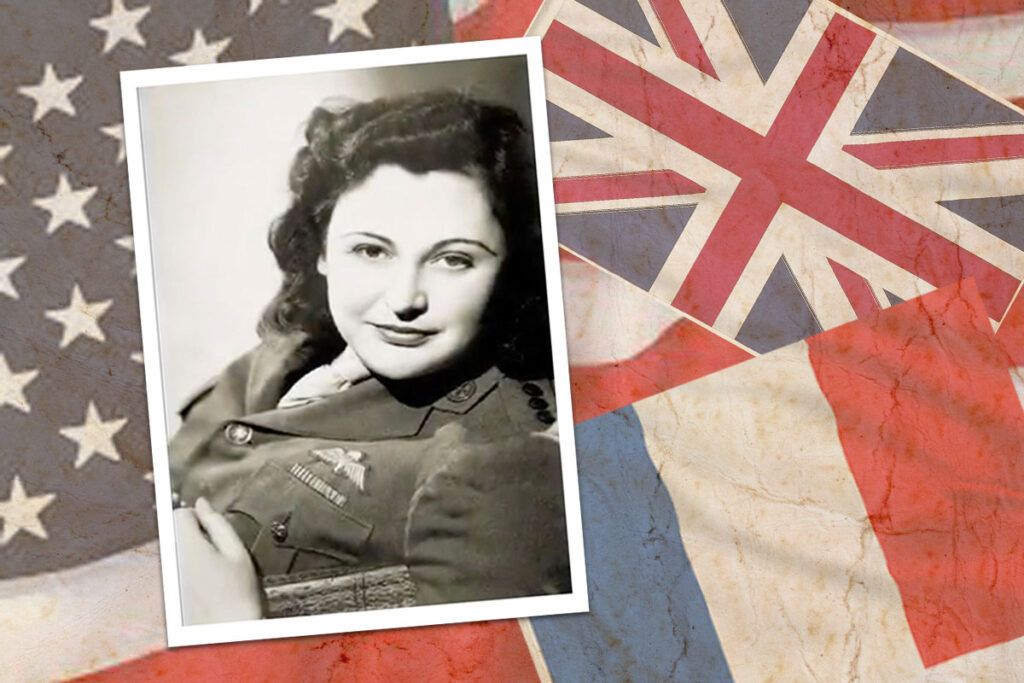

The Gestapo didn’t know who she was. The Nazi secret police who were notorious for capturing Allied spies only knew of her legend — a beautiful and mysterious woman who would slip away from capture each time they closed in. The Gestapo referred to her simply as “The White Mouse” and reportedly put her at the top of their “most wanted list” with a price of 5 million francs on her head.

Their mystery woman was New Zealand-born and Australian-raised. She was a nurse who had run away from her Sydney home at 16 and studied journalism in London at 20. She was a freelance journalist posted to Paris in the 1930s during a time when the city was the epicenter of the fashion industry. And she was a spy — one who was motivated to fight against the Nazis in World War II after witnessing one cataclysmic event while on assignment in Vienna.

In the middle of the street, she observed the Schutzstaffel (SS) — the Nazis’ paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler — tie Jewish people to a large wheel and torture them. It was this moment when Nancy Wake made a decision that would change the course of her life. “I stood there and I thought, ‘That’s dreadful, I couldn’t whip a cat,’” Wake recalled to ABC News (Australia). “If ever I can do something one day, I’ll do it.”

It wouldn’t take long for Wake to have her chance to fight against fascism.

She married a wealthy industrialist named Henri Fiocca in 1939. They entertained dinner guests with champagne and caviar in their luxury apartment overlooking the Marseille harbor. When Germany invaded France six months later, Wake used her wealth and social status to help shield her activities with the French Resistance. She served as a courier delivering messages to underground groups in the Marseille area. Her husband provided support with his financial resources, including purchasing an ambulance used to transport Jewish refugees, Royal Air Force pilots who’d been shot down, and burned spies along the Pat O’Leary Line. The escape route had safe houses along the way to the Pyrenees mountains, which the French Resistance used to help allies and refugees reach safe haven in Spain.

“The Germans couldn’t come up and get us and they couldn’t send the police dogs up there because they couldn’t climb up from the rocks,” Wake told an interviewer in 2003. “So we used to be there looking after the people who wanted to escape from France. And if we had a big party we used to stand up on the Pyrenees and throw all the empty bottles and cans down on the Germans. We did that for over two years.”

The threat of the Nazis and their suspicions culminated when she was apprehended in 1942 and spent four days being interrogated. The Germans didn’t realize they had caught the White Mouse, so when Albert Guérisse, a Belgian doctor who organized the Pat O’Leary Line, told the German officer she was his mistress and her story was false because she was lying about her infidelity, the German policeman believed him and set her free.

“It was much easier for us, you know, to travel all over France,” she told an interviewer for Australian television, according to The New York Times. “A woman could get out of a lot of trouble that a man could not.”

Wake fled to Spain in May 1943, but her husband, who had promised to follow behind, was captured and executed. Wake was recruited to join the Special Operations Executive (SOE), a British paramilitary unit that specialized in commando operations. She was “a real Australian bombshell,” recalled Vera Atkins, one of the SOE officers of the French section. “Tremendous vitality, flashing eyes. Everything she did, she did well.”

In April 1944, at 31 years old, having completed her commando training, Wake dropped by parachute into the Auvergne region along with French resistance circuit leader Maj. John Farmer.

“Over civilian clothes, silk stockings and high heels I wore overalls, carried a revolver and topped the lot with a camel-haired coat, webbing harness and a tin helmet,” she said, according to the Independent.

Her parachute tangled in the branches of a tree and one Frenchman commented that he hoped all the trees “could bear such beautiful fruit.” In her blunt and straightforward way she replied, “Don’t give me that French shit.”

Among only 39 women and 430 men to parachute into France to make preparations for D-Day, Wake linked up with the Maquis, a 7,000-member partisan force. She organized parachute drops of supplies, weapons, and equipment, operating under the alias “Madame Andrée” and the code name “Witch.” When the roads were too dangerous to travel by vehicle, she bicycled more than 300 miles in three days to find replacement codes for their radios to remain in contact with London.

Following World War II, Wake was named a heroine of the French Resistance and was awarded civilian honors by the US, Britain, and France. She blamed herself for the death of her husband and spent a large portion of the remainder of her life sipping gin and tonic from “Nancy’s Corner” at the Stafford hotel in London. “There was no point in keeping them,” Wake said, referring to how she funded her lifestyle by selling her war medals. “I’ll probably go to hell and they’d melt anyway.”

Nancy Wake died on Aug. 7, 2011, at 98 years old. “When I die,” she had requested, “I want my ashes scattered over the hills where I fought alongside all those men.”